New Alan Turing £50 note enters circulation

The release date coincides with what would have been the computer pioneer and wartime codebreaker's birthday.

It means the Bank's entire collection of currently-printed banknotes is made of plastic for the first time.

Paper £50 and £20 notes will no longer be accepted in shops from October next year, although post offices will still exchange them.

The Bank of England's own counter can also swap any old notes for their face value.

The BBC was given rare access to the De La Rue banknote printing plant in Essex, where the new Bank of England note is being produced.

As many as five million new banknotes can be produced in a day, with 1.3 billion rolling off the machines in a year. Various currencies are produced at the site and the notes are sent to countries around the world.

Despite cash use falling for purchases, particularly during the pandemic, there is still a growing demand for banknotes. Population growth and hoarding are among the reasons for the rising requirement.

The £50 note is the least frequently used of the Bank's collection. Its future has been called into question in the past, with one review describing it as the "currency of corrupt elites, of crime of all sorts and of tax evasion".

However, there have still been 357 million of them in circulation this year - the equivalent of one in 13 banknotes.

"They are used more often than people realise," said the Bank of England's chief cashier, Sarah John, whose signature is on the note.

"A lot of tourist spending is dependent on £50 banknotes. They are also used as a store of value."

Withdrawn notes

The old, paper £50 banknotes - first issued in 2011 - are no longer being produced, and will be withdrawn by the end of September next year. They feature steam engine pioneers James Watt and Matthew Boulton.

Paper £20 notes, featuring the portrait of economist Adam Smith, will also be withdrawn at the same time. The replacement polymer version, which shows artist JMW Turner, went into circulation in February last year.

The polymer versions should last two-and-a-half times longer than their predecessors, are harder to forge, and should also survive a spin in the wash.

There have been some concerns raised about plastic banknotes, from the traces of animal products used in their production, to anecdotal worries about the notes sticking in wallets and purses.

Ruth Euling. managing director of De La Rue Currency, said it was "more challenging" to produce polymer notes, but it made financial sense.

"Making cash more efficient is also an important part of keeping cash alive," she said.

Although very few ATMs issue £50 notes, various High Street banks are issuing the new banknote from their counters from Wednesday.

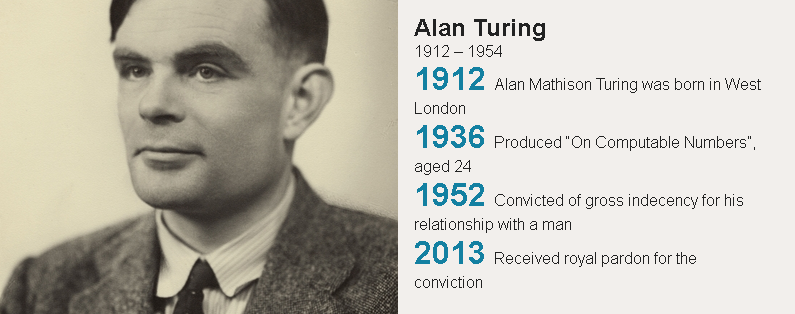

The note features and celebrates the work of Alan Turing, educated in Sherborne, Dorset, who helped accelerate Allied efforts to read German Naval messages enciphered with the Enigma machine, and so shortening World War Two and saving lives.

He was also pivotal in the development of early computers, first at the National Physical Laboratory and later at the University of Manchester.

The choice to place him on the note is also designed to promote diversity.

The Bank is flying the Progress Pride flag above its building in London's Threadneedle Street on Wednesday to recognise improvements since his appalling treatment by the state for being gay. In 2013, he was given a posthumous royal pardon for his 1952 conviction for gross indecency.

He had been arrested after having an affair with a 19-year-old Manchester man, and was forced to take female hormones as an alternative to prison. He died at the age of 41. An inquest recorded his death as suicide.

In keeping with his work, the new note includes security features, similar to other notes, such as holograms, see-through windows - based partly on images of the wartime codebreaking centre at Bletchley Park - and foil patches.

The UK's intelligence agency GCHQ has also unveiled an artwork of Alan Turing's portrait inside the wheels of the codebreaking British Bombe machine, placed in the middle of its headquarters to celebrate his legacy,

Jeremy Fleming, GCHQ director, said: "Alan Turing was a genius who helped to shorten the war and influence the technology that still shapes our lives today."

Snapchat has also created a history of his work which can be viewed via augmented reality.