‘Many hold Gove responsible’: education guru sets out what’s wrong with England’s schools

The veteran educationist Sir Tim Brighouse is in an optimistic mood. This may be a period of “doubt and disillusion”, especially as Covid threatens to disrupt another school year, but in his view such times inevitably lead to change. With that in mind, he has just co-authored a sweeping 600-page overview of modern education policy, with suggestions he hopes will contribute to a new direction.

Written with the curriculum expert Mick Waters, About Our Schools divides recent history into two eras: a postwar age of “hope and optimism”, in which teachers were pretty free to do what they liked, followed by a post-Thatcher age of “markets, centralisation and managerialism”, in which the influence of inspections and league tables became all-pervasive and individual ministers could decide how skills such as subtraction should be taught in every classroom in England.

The language used to describe the two ages is so leading that you could be forgiven for thinking Brighouse was a fully paid-up member of what the former education secretary Michael Gove, who straddles the book like a malign colossus, used to dismiss as “the blob”, after a 1958 science fiction film in which a gelatinous life form (in this case the progressive education establishment) engulfs everything it touches.

But he is adamant that he would fit into either age. “I don’t want anyone thinking we are just romantic oldies looking back at a forgotten period,” he says. “Many good things about that postwar period were poor. Teaching wasn’t good enough and there was a less clear definition of what a good school was.

“But reforms that helped to bring improvement have been poisoned by over-emphasis on autonomy and a devil-take-the-hindmost approach. Accountability has gone too far and become punitive.”

Mick Waters, former director of curriculum at the Qualifications and Curriculum Authority and co-author of About Our Schools.

Mick Waters, former director of curriculum at the Qualifications and Curriculum Authority and co-author of About Our Schools.

His own professional life is steeped in the old local education authority model – he was chief education officer (when such things existed) in Birmingham and Oxfordshire. He also led the London Challenge, arguably one of the most successful education initiatives of the past three decades, and was a reformer who published exam results in Oxfordshire well before they were a national reality.

But, as the book painstakingly points out, schools in England now have too much central government control, an incoherent jumble of different academy chains and local authorities, exams with grading systems designed to write off a significant minority of children as failures, undervalued technical and vocational education, inadequate support for children with special needs, and performance measures that incentivise unethical behaviour, in particular exclusion and “off-rolling” of the most vulnerable pupils.

It’s an accurate and disturbing picture – and should be a call to arms for anyone genuinely interested in effective policy-making. Brighouse and Waters’ numerous solutions, which range from taxing private schools – to subsidise poorer children’s education – to cracking down on admissions and exclusions “dirty tricks” and coaxing every school into some sort of local partnership trust (which sounds suspiciously like the mass academisation plan that had to be ditched by the Lib-Con coalition government), are logical and radical – so much so they seem unlikely to catch on, although Labour, with its current policy vacuum, might take note.

Attempting to tease out why such sensible and fair policy ideas may never see the light of day should be the question of the moment. The book sheds light on this, too, thanks to interviews with most of the education secretaries of the past three decades, plus a handful of Ofsted chiefs.

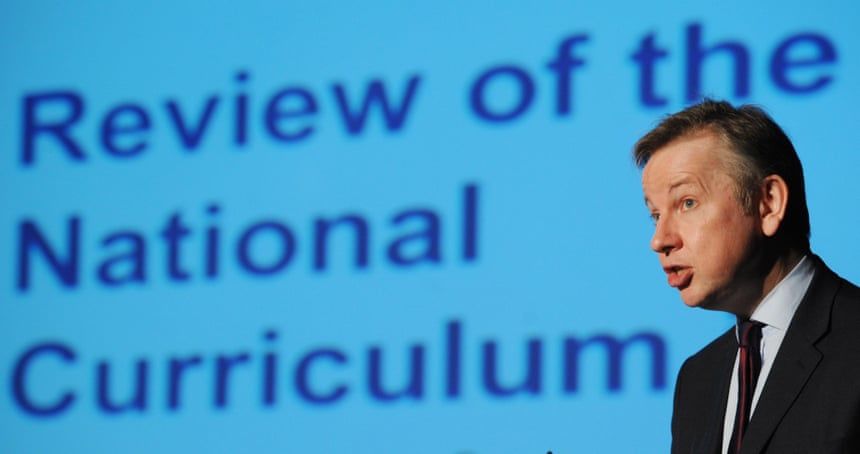

The former education secretary Michael Gove in 2011 announcing a review of the national schools curriculum.

The former education secretary Michael Gove in 2011 announcing a review of the national schools curriculum.

The problem is politics. When the former Labour prime minister Jim Callaghan made his famous Ruskin speech in 1976 challenging the lack of accountability in education, in effect the starting point of reform, the secretary of state had only three powers over schools. Today he or she has more than 2,500.

Thousands of schools are now run from Whitehall through academy chains. Little real autonomy exists at a local level, and every head is at the mercy of whoever is in power and the appetite of Downing Street for dramatic change. So much so, that some professional interviewees were reluctant to be quoted for fear of the consequences.

The average life span of an education secretary is just over two years – enough time for a few “launches and logos”, according to the authors – and this has inevitably led to most simply tinkering with the direction of travel of their predecessors.

As the former Labour education secretary Charles Clarke explains, “realpolitik” interferes; ideas get abandoned or shoved into a “too difficult box” to be left to a successor, who then works through the same cycle. Dealing with the archaic system of grammar schools and the 11-plus test is just one example of this.

And while some education secretaries – such as Ken Baker, who ushered in an era of choice, league tables and inspections; David Blunkett, with his drive on standards; and Ed Balls, who widened his department’s focus to include children and families as well as schools – made a tangible difference, none really questioned the underlying problems with the system.

Talking to them for the book, “very few regretted anything they had done,” says Brighouse. “Most regretted things they hadn’t done and that they didn’t have more power. While all agreed that schools should be vehicles for greater equity, equality and social mobility, a lack of agreement about the purpose of schooling makes it very hard to define what those aims actually mean in practice.”

The former Labour education secretary Charles Clarke: ‘realpolitik interferes’.

The former Labour education secretary Charles Clarke: ‘realpolitik interferes’.

And then there is Michael Gove. Even though he only answered questions from the authors in writing, and did express regret for the way he cancelled the Building Schools for the Future programme in 2010, the anecdotes of others are littered with his influence.

Whether it is Gove’s own assertion that “there is no such thing as a smooth revolution” (reform is by necessity untidy), or his former adviser Sam Freedman’s regret that more consensus was impossible because of Gove’s (and no doubt Dominic Cummings’s) penchant for waging a public fight in the media, or the former Ofsted chief inspector Michael Wilshaw recounting that Gove did not want local authorities inspected because he wanted them to “wither on the vine”, Gove’s legacy is everywhere.

It has not been a positive one, conclude the authors. “Many people interviewed for the book hold Gove responsible for some of the fundamental problems with schooling today – the fractured system, high exclusions and unsuitable curriculum,” they write.

These are all problems Brighouse and Waters would seek to address at a post-Covid moment when people are yearning for what they describe as a “a new educational age – a time of hope, ambition and collaboration”.

The former Ofsted chief Sir Michael Wilshaw: Gove wanted local authorities to ‘wither on the vine’.

The former Ofsted chief Sir Michael Wilshaw: Gove wanted local authorities to ‘wither on the vine’.

But how to translate that yearning into real policy change? The book contains a telling anecdote from Brighouse’s days as the London schools commissioner, when he was asked by the then prime minister, Tony Blair, if there was anything he wanted to add to the London Challenge prospectus.

Brighouse’s suggestion that they should include something about the chaotic state of secondary school admissions in the capital was “greeted with an audible silence”, after which, he admits, he backed off the subject.

“I have no idea how often I spoke truth to power; I am not sure I did enough. I didn’t fight hard enough over admissions, and I am conscious now that I should have done more,” he says. “I have never felt that I am pleased with what I have achieved because we didn’t address admissions or exclusions and you see the results of that now in the children who are effectively forgotten by the system.”

This may explain why, amid all the “building back better” policy solutions that the book suggests, he instantly settles on a plan for the “open school”, a parallel version of the Open University, as his top priority.

The open school would build on the pandemic’s lessons about digital learning and create a national virtual school to help offset disadvantage, include children who are out of school, and provide enhanced opportunities for all.

It would wrap around a system guided by very different principles from the ones we see today: a new consensus on the purpose of schooling, a national cross-party commission to take a balanced 10-year view of education policy, schools being judged in groups rather than alone, with inclusion and wellbeing incentivised as well as exam results. Naturally there would be an enhanced role for the local authorities, which would be responsible for holding the new partnerships to account, in effect restraining central government power.

Brighouse’s optimism is rooted in the parallels he sees between the moment of Callaghan’s Ruskin speech, a crucial starting point of the book’s journey, and today. “Everyone knew something had to change but it took a decade before the ideas were shaped into the 1988 Education Act,” he says.

“Change comes from a conjunction of individuals, ideas and an environment that is conducive,” he suggests, pointing to an example from his own local community about how this might work in practice. His wife, Liz, has long been an Oxfordshire county councillor and is now part of the Fair Deal Alliance, a coalition cabinet of Labour, Liberal Democrats and the Greens.

In his fantasy future he sees a closer alliance between the opposition parties in favour of electoral reform and consensus on some big policy ideas, hopefully including some from the book.

“Today feels like 1976 when Callaghan made his speech. It took time, but change came in the end and this moment feels very similar, so even if it takes five to 10 years, we will have been happy to give these ideas a push and contributed to that.”