Spring migration in Saudi Arabia, part one

In mid-February this year an old mate of mine, Paul Cook, asked me if I fancied working for him doing a bird survey in a little-known part of the central Saudi Arabian desert. It may take quite some time for the scars to heal where I bit his hand off in my haste to reply! Just a couple of weeks later, after a feverish scramble to renew both our passports and have our visas processed at the Saudi embassy in London, the two of us were sat in a suburban town park a few hours' drive north of Riyadh with our project manager. The two of them would only be with me a few days, showing me the ropes on my survey site just outside of town, before they would be heading off 800 km north to a second location, somewhere near the Jordanian border.

It was dark, 7 pm, and as we sat on a bench facing towards rows of laurel trees and an acre or two of ornamental lawn, I had no idea of what I was about to experience there over the following six-and-a-half weeks. The significance of where we sat on that first evening will become more apparent in the second instalment of this account – suffice it to say for the moment, my expectations were certainly being held well in check, based on the 'habitat' (if you can call it that) which presented itself in front of me.

I'm not in a position to divulge the precise location, except to say it was a desert area that had not been visited by any birder previously. Initially at least, my work day consisted in having to do three-hour watches from a series of different vantage points (VPs) spaced out across what at first might best be described as a somewhat daunting, largely featureless, inhospitable wilderness. Certainly, there were mornings at the beginning – arriving on site at the crack of dawn in off-road vehicles – when it appeared to all intents and purposes that we were driving over a cross between Blakeney Point and the Moon. Yet, day by day, it began to grow on me, and after about 10 days I really began to appreciate my good fortune in having a patch with a number of interesting features that gave each of my vantage points something of their own unique, special character.

Though having no pretensions to be a geologist myself, I did think it might have been nice to have been in the presence of someone who could have speculated about the enormous elemental forces that shaped the terrain the way that it had – especially to give me some sort of idea as to how old this landscape was. Anyhow, just to be aware of these thoughts lent a frisson of awe to the birding experience – even on the quietest days, sitting in the silence, contemplating the enormity of time in relation to my little human life span, was to feel elevated to a dimension outside the usual day-to-day concerns.

It was soon quite clear that my site was not a place of significant interest for raptor migration – not in the late March to early May period that I was there, anyway. Indeed, on the occasion my only Short-toed Snake Eagle of the survey appeared directly overhead, I said to my two colleagues up country, I couldn't have been more taken aback if an alien spacecraft had appeared in its stead!

Long days in the field in temperatures up to 38c could have worn a person down after a while, but for the fact there was plenty of other avian interest on offer to keep me company. To begin with there were a half-dozen larks that somehow eke out a living throughout the year in this harshest of environments and they were a more or less constant presence and a delight. The prime example of this was the iconic Greater Hoopoe-Lark. A haunting, atmospheric sound of two or three of my VPs on the flatter eastern plain was the rising high-pitched stanzas of its territorial song – occasionally given from the ground or a bush, but most frequently accompanied by the characteristic tumbling song-flight.

The unique bird that is Greater Hoopoe-Lark

The unique bird that is Greater Hoopoe-Lark

Both Temmincks and Thick-billed Larks were well-represented on my Saudi patch, affording plenty of opportunities to witness aspects of their family life that I wouldn't expect to see on a shorter trip, including interaction between adults and young. Crested, Desert and Bar-tailed Larks made up the remainder of the family.

One of the most noticeable breeding birds encountered daily was 'Southern' Grey Shrike. There were quite a number of very hot hours, especially during the afternoons, when there would be virtually no birds whatsoever to keep me entertained other than one or two of these formidable predators going about their business from acacia bush to ground, collecting large insects to take back to their broods of hungry young. Sometimes pairs were seen asserting their dominance over other shrikes that occasionally passed through their territory – Masked, Woodchat, Isabelline, Lesser Grey and Red-backed Shrikes were all seen off.

White-crowned Wheatear was also the only member of its family staying to breed while its congeners passed through on their way north. They could be found not uncommonly on the steep slopes of the western edge of the site and they could be quite bold and confiding at times, the young in particular being one of the birds I had the most frequent intimate close contacts with as they occasionally sat next to me, curiously contemplating what this bizarre human creature was doing sitting out in an environment that seemed so oppressingly hostile to his presence.

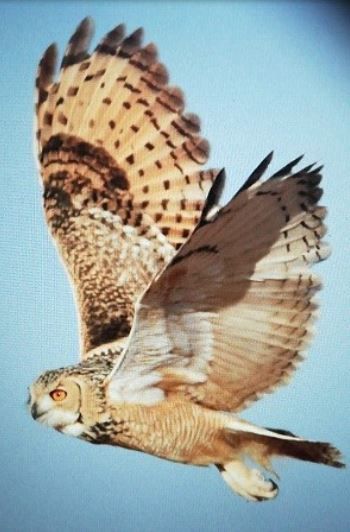

At the opposite end of the approachable spectrum, Cream-coloured Courser and Pharaoh Eagle-Owl both had a tantalising, mysterious and elusive presence in the area I was working. I saw the former on a dozen or more occasions, but they were always such ephemeral encounters – if not at a kilometre range shimmering like little mirages in the desert heat, then extremely brief, moderately close-range affairs that ended when the bird or the pair somehow managed to slink away across the stones, seemingly adopting invisibility cloaks in a matter of seconds. Pharaoh Eagle Owl I did manage to see extremely well shielded by an acacia for an hour on one occasion after a month of seeing evidence of its presence in the form of pellets and droppings, but after that ... never again.

Indescribably brilliant. A Pharaoh Eagle-Owl in flight

Indescribably brilliant. A Pharaoh Eagle-Owl in flight

Migration through the desert – what a remarkable thing! The phenomenon, performed twice annually by millions of birds across the Northern Hemisphere is particularly hard to fathom as a human being when you spend six weeks watching it occurring in an environment such as this. The most conspicuous migrants on my patch by far, and in being diurnal migrants in some ways the most compelling, were bee-eaters. From the very first day to the very last, there wasn't a single day when I didn't have at least one European Bee-eater and, on almost every single day, at least one Blue-cheeked also.

Isabelline and Pied Wheatears – both very fine birds in their own right – also had a sustained presence from start to finish, but unlike those two, European Bee-eaters reached an ornithologically mind-blowing peak for about a week during a period of quite strong, blustery north-easterly headwinds around the second week of April. For four days in a row, they brought me century counts, one of the days being converted to a double century, including a quite memorable flock of 70 flying steadily north just above the ground as the light was coming up. Although Blue-cheeked were generally only about a quarter as numerous as their cousins, they did seem to hang around for greater periods, especially in the first fortnight, lighting up the desert with their luminous colours as they hunted insects in loose parties low to the ground.

European Bee-eater was easily the most numerous migrant on Graham's patch this spring

European Bee-eater was easily the most numerous migrant on Graham's patch this spring

Much of what I have to say about the passerine migration I'm going to leave to Part Two of this account. The number of small songbirds I encountered in Saudi Arabia was much higher in the town parks than it was in the desert wadis, though of course a special admiration was naturally bestowed upon those individuals that found themselves pitching up in the latter situation simply because of its apparently inherent austerity. I have to say, though, this was just my point of view, for the birds themselves seemed quite happy with it – and they have been doing it for thousands of years, so what do I know!

Aside from the lack of water (the prime reason for my anthropomorphic concern) there was certainly no shortage of insects. The first day on the patch saw the incredible aftermath of a plague of locusts that had hit the Arabian Peninsula in the months prior to my arrival. Tens of thousands of corpses lay end on end in tyre tracks throughout the desert where one didn't have to be a professional detective to work out that the swarms must have been so dense that they didn't have time to get out of the way of the wheels of the occasional car or truck that had passed this way, moving between the nomadic farmsteads that were strung out across the sandy terrain. It was several weeks though before I made the connection between the crushed insects and the myriad lines of tiny creatures that were the next generation offspring munching and hopping their way northwards over the landscape.

As well as the locust plague, in places there were huge numbers of other grasshoppers and crickets, which provided many a snack for the various migrant shrike species that became increasingly numerous towards the back end of April.

Flora in some of the wadis was impressive.

Flora in some of the wadis was impressive.

Perhaps the best way to portray the minutiae of the bird migration through the desert is to give a couple of examples of moments that stood out for me personally. Two in particular occurred with birds I thought I was already exceedingly familiar with. I remember one very hot, silent, windless morning sitting gazing out at a vast stony nothingness as far as the eye could see, feeling myself slowly, mentally beginning to disengage with waking thoughts, when suddenly what sounded like a loud rush of air almost made me leap clean out of my chair in startled surprise. All it was turned out to be the sound of the air displaced by the wingbeat of a Swallow and the accompanying snap of its bill as it took a fly right next to my shoulder before continuing on its merry way without a single glance behind. Ten seconds later it had disappeared from sight.

On another occasion of hot, shimmering, quiet stillness, sat at the edge of one of my loftier VPs, picking up a tiny dot approaching my station from below. Gradually getting closer over a minute or more before eventually reaching the top of the rise, pausing for a second and then off it went again, low over the stones, watched all the way out of sight, this one gone in thirty seconds. It was a Willow Warbler – and in that second I registered its face as it paused on the cliff edge, I swear it was grinning!

Some of the local Bedouin-style farmsteads housing various sheep breeds and small groups of camels. Naturally the presence of a strange Westerner dressed in shorts, T-shirt and sunglasses and sporting binoculars and a telescope must have been something of an intriguing sight to them, to say the very least. They were very friendly, I must say, but whenever one would come up and try to engage me in conversation I had to pass them on to my Pakistani back-up driver who was well-versed in the local language, even if his English was somewhat limited. To simplify things across the board I'd usually say I was watching birds coming from Africa and flying to Russia and I guess in a very broad sense from my own point of view that helped situate me geographically in the very centre of this unfathomably magnificent, mysterious process I was engaged in witnessing.

There were at least 10 individuals of four warbler species in this acacia tree on 22 April: Barred, Upcher's, Eastern Olivaceous, and five Willow Warblers, plus a Common Whitethroat.

There were at least 10 individuals of four warbler species in this acacia tree on 22 April: Barred, Upcher's, Eastern Olivaceous, and five Willow Warblers, plus a Common Whitethroat.

This sense of time and place was most apparent the morning I picked up a line of unidentifiable dots against the light, due south of my sitting position, at least a kilometre away. It took five minutes of nagging doubt and intrigue before they finally materialised as a party of 17 European Rollers, flying at a 45-degree angle from me across the desert. The ever-handy BWP I had open on my laptop virtually every night to background research the timings and the directions of the birds I was seeing throughout the trip to put my sightings in perspective did it again, confirming yes, that was exactly what was happening. A week ago these birds were in Somalia. A week from now, where would they be? Iran? Iraq? Turkey? Kazhakhstan? Or even Russia? Again, who knows? All I could do was wish them well on their way.