Signal would 'walk' from UK if Online Safety Bill undermined encryption

If forced to weaken the privacy of its messaging system under the Online Safety Bill, the organisation "would absolutely, 100% walk" Signal president Meredith Whittaker told the BBC.

The government said its proposal was not "a ban on end-to-end encryption".

The bill, introduced by Boris Johnson, is currently going through Parliament.

Critics say companies could be required by Ofcom to scan messages on encrypted apps for child sexual abuse material or terrorism content under the new law.

This has worried firms whose business is enabling private, secure communication.

Element, a UK company whose customers include the Ministry of Defence, told the BBC the plan would cost it clients.

Previously, WhatsApp has told the BBC it would refuse to lower security for any government.

'Magical thinking'

The government, and prominent child protection charities have long argued that encryption hinders efforts to combat online child abuse - which they say is a growing problem.

"It is important that technology companies make every effort to ensure that their platforms do not become a breeding ground for paedophiles," the Home Office said in a statement.

It added "The Online Safety Bill does not represent a ban on end-to-end encryption but makes clear that technological changes should not be implemented in a way that diminishes public safety - especially the safety of children online.

"It is not a choice between privacy or child safety - we can and we must have both."

Child protection charity the NSPCC said in reaction to Signal's announcement: "Tech companies should be required to disrupt the abuse that is occurring at record levels on their platforms, including in private messaging and end-to-end encrypted environments."

But the digital rights campaigners the Open Rights Group said it highlighted how the bill threatened to "undermine our right to communicate securely and privately".

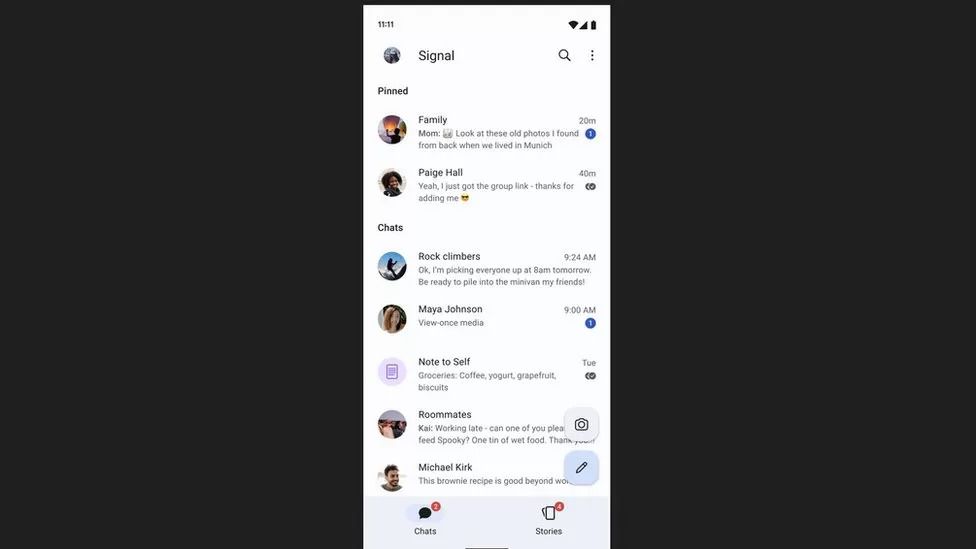

Signal messages are protected by end-to-end encryption

Signal messages are protected by end-to-end encryption

But Ms Whittaker told the BBC it was "magical thinking" to believe we can have privacy "but only for the good guys".

She added: "Encryption is either protecting everyone or it is broken for everyone."

She said the Online Safety Bill "embodied" a variant of this magical thinking.

Signal has had over 100 million app downloads on the Google store alone.

It uses end-to-end encryption, a system where messages are scrambled so that even the company operating the service cannot read them.

Operated by a Californian based not-for-profit organisation, the app's users include journalists, activists and politicians.

WhatsApp also uses end-to-end encryption, as does Apple's iMessage system and optionally Facebook and Telegram.

Apple had proposed a system where messages sent from phones and other devices would be scanned for child abuse images before being encrypted but abandoned the plans following a backlash.

Called client-side scanning, some have said this is the approach that tech firms may end up having to use - but critics argue it effectively undermines the point of encryption.

It would in effect turn everyone's phone into a "mass surveillance device that phones home to tech corporations and governments and private entities", Ms Whittaker said.

'Privacy promises'

Ms Whittaker said "back doors" to enable the scanning of private messages would be exploited by "malignant state actors" and "create a way for criminals to access these systems".

Asked if the Online Safety Bill could jeopardise their ability to offer a service in the UK, she told the BBC: "It could, and we would absolutely 100% walk rather than ever undermine the trust that people place in us to provide a truly private means of communication.

"We have never weakened our privacy promises, and we never would."

Matthew Hodgson, chief executive of Element

Matthew Hodgson, chief executive of Element

Matthew Hodgson chief executive of Element, a British secure communications company, said the threat of mandated scanning alone would cost him clients.

He argued that customers would assume any secure communication product that came out of the UK would "necessarily have to have backdoors in order to allow for illegal content to be scanned".

It could also result in "a very surreal situation" where a government bill might undermine security guarantees given to customers at the MoD and other sensitive areas of government, he added.

He also said the firm might have to cease offering some services.

Child safety

Ms Whittaker said: "There's no-one who doesn't want to protect children," adding: "Some of the stories that are invoked are harrowing."

When asked how she would respond to arguments that encryption protects abusers, Ms Whittaker said she believed that most abuse took place in the family and in the community - where she argued the focus of efforts to stop it should be.

She pointed to a paper by Professor Ross Anderson, which argued for better funding of services working in child protection and warned that "the idea that complex social problems are amenable to cheap technical solutions is the siren song of the software salesman".