Patients at risk as NHS and care 'gridlocked'

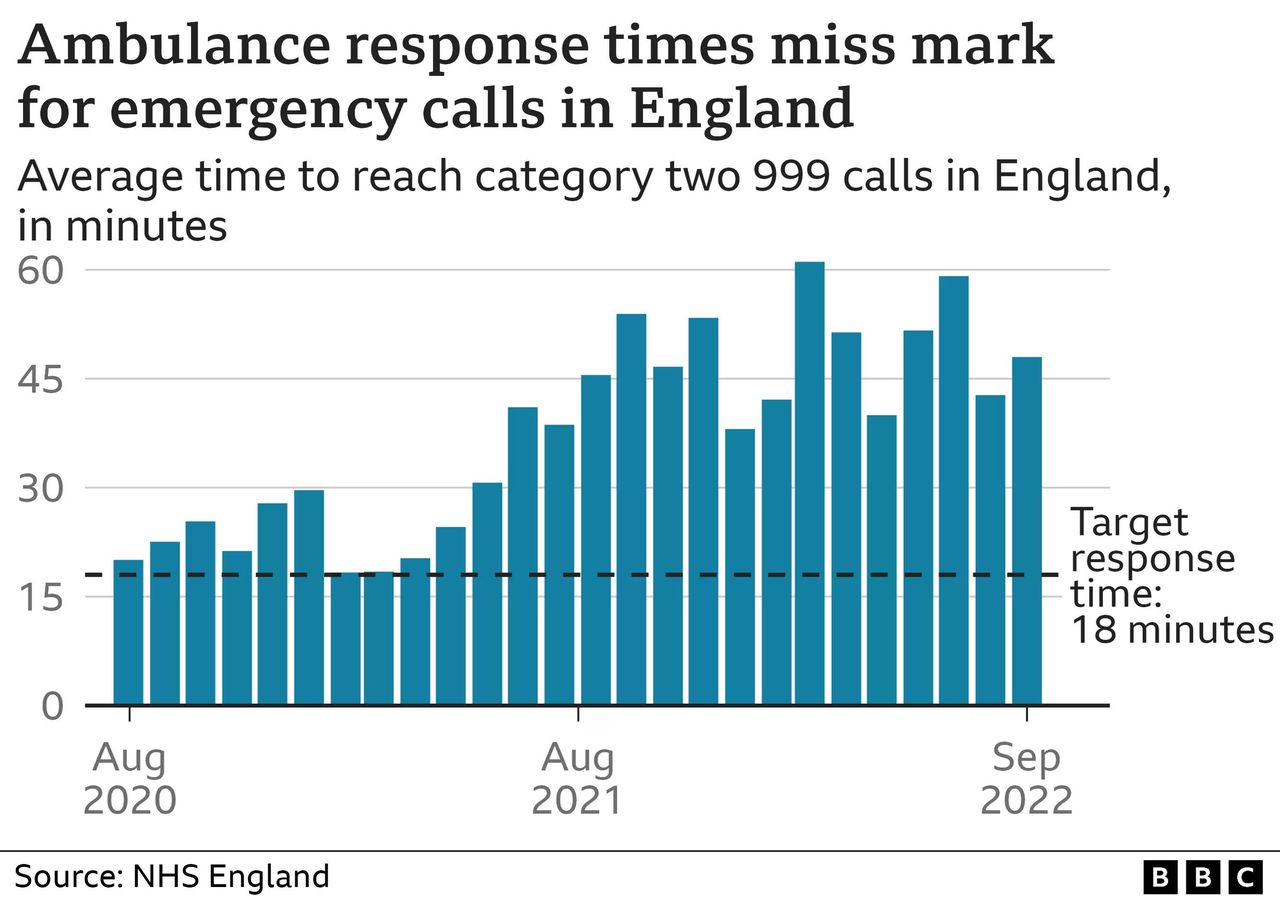

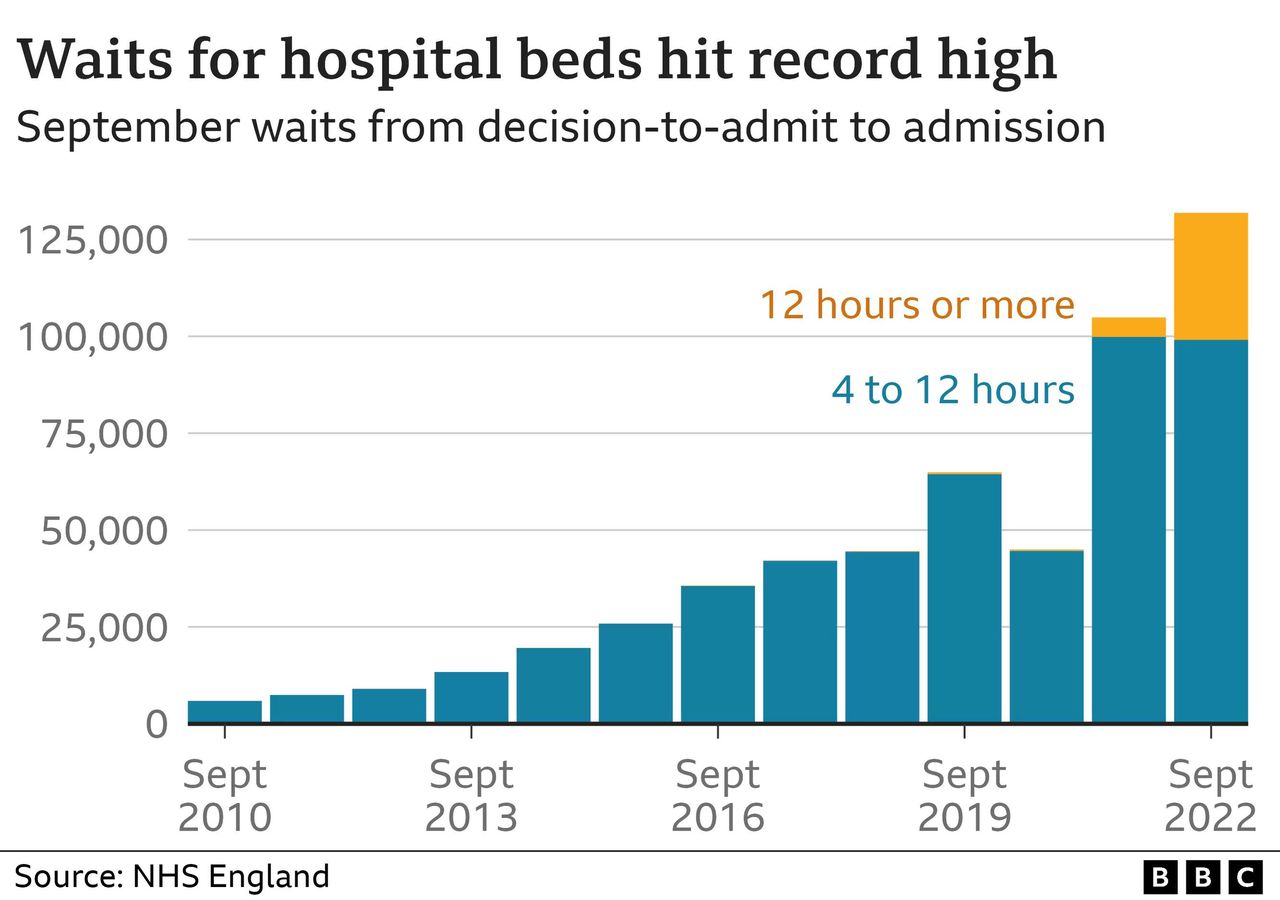

The Care Quality Commission's annual report warned the problem was creating long waits for ambulances and in A&E.

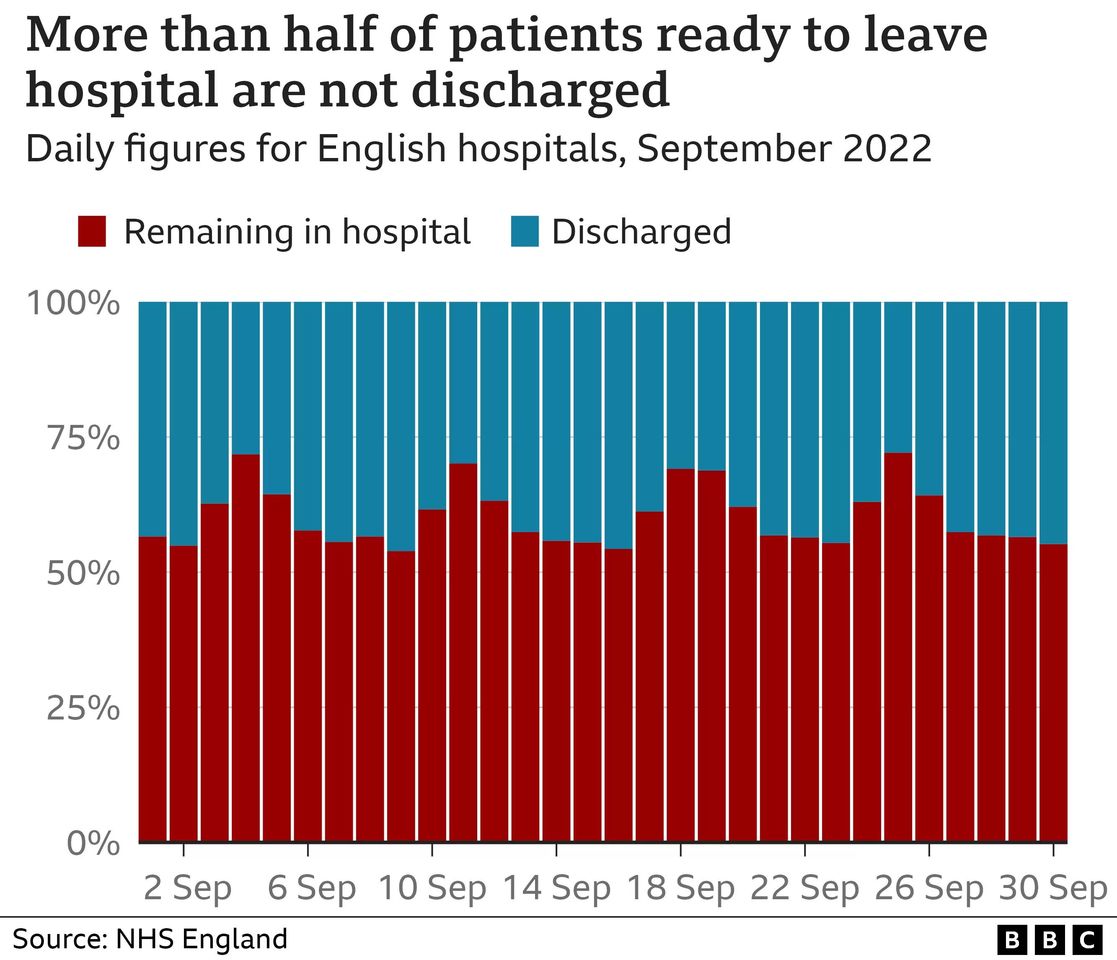

A major factor is most patients cannot leave hospital when they are ready, it said, because of a lack of support in the community.

The system, the CQC said, could no longer operate effectively.

"People are stuck - stuck in hospital because there isn't the social-care support in place for them to leave, stuck in emergency departments waiting for a hospital bed to get the treatment they need and stuck waiting for ambulances that don't arrive because those same ambulances are stuck outside hospitals waiting to transfer patients," chief executive Ian Trenholm said.

This winter would be particularly tough, he warned, and he was worried about how the health and care systems would cope.

Alongside the delays in accident-and-emergency departments and with 999 services, 500,000 people are waiting for council-funded care - an increase from just under 300,000 in a year.

The CQC report blamed staffing shortages, with one in 10 posts in both the NHS and social-care sector vacant.

Maternity care 'unacceptable'

The regulator was also heavily critical of maternity care, pointing out only two out of five services were rated good enough.

The signs were services were becoming worse, it added. "It's unacceptable," Mr Trenholm said.

It comes after an inquiry into maternity care at East Kent Hospitals University NHS Foundation Trust found evidence of significant harm to babies, due to a "clear pattern of suboptimal care" during an 11-year period from 2009.

The review, published on Wednesday, said up to 45 babies may have survived with better care.

Mr Trenholm said maternity services, like the rest of the system, suffered from a lack of staff but there also seemed to be a cultural problem where the concerns were not being listened to as they should or prompting the necessary response.

The East Kent report comes just months after similar failings were identified at Shrewsbury and Telford Hospital NHS Trust.

The wider issues across health and care, Mr Trenholm said, were undoubtedly linked to "historic under-investment" - and without action, would only worsen.

This would be especially visible in poorer areas, where access to care outside hospitals was most under pressure, he said.

In addition to the increased risk of harm, more people would be driven out of the labour market through ill health or because they were supporting family members who needed care, Mr Trenholm added.

Louise Ansari, from the patient group Healthwatch England, said the findings echoed what many patients had been telling her.

The problems would be putting "lives at risk" and widening health inequalities, she said.

"It's starting to affect the public's confidence that the NHS will be there for them when they need it," Ms Ansari added.

NHS England medical director Prof Sir Stephen Powis accepted it was going to be an "incredibly challenging" few months.

Extra support was being provided to keep patients out of hospital, he said, including the rollout of rapid-response teams to treat patients at home after incidents such as falls.

"NHS staff are working hard to keep patients safe despite the record demand and pressures," Sir Stephen added.