Is the nude selfie a new art form?

"Love, lust, pleasure, desire, beauty, anatomical study, self-expression, egotism… The impulses behind sending nudes are many. Creating nudes and sharing them seems to be part of human nature." So begins Karla Linn Merrifield, in the first contribution to a new anthology entitled Sending Nudes. A collection of poems, stories and memoir on the subject, it takes a long hard look at the contemporary – and seemingly timeless – habit of sharing images of the naked human form.

The idea came to editor Julianne Ingles after a short story entitled Send Nudes was submitted for a previous anthology she was working on. "I thought [the topic] could be explored, that other people would have stories and poems," says Ingles.

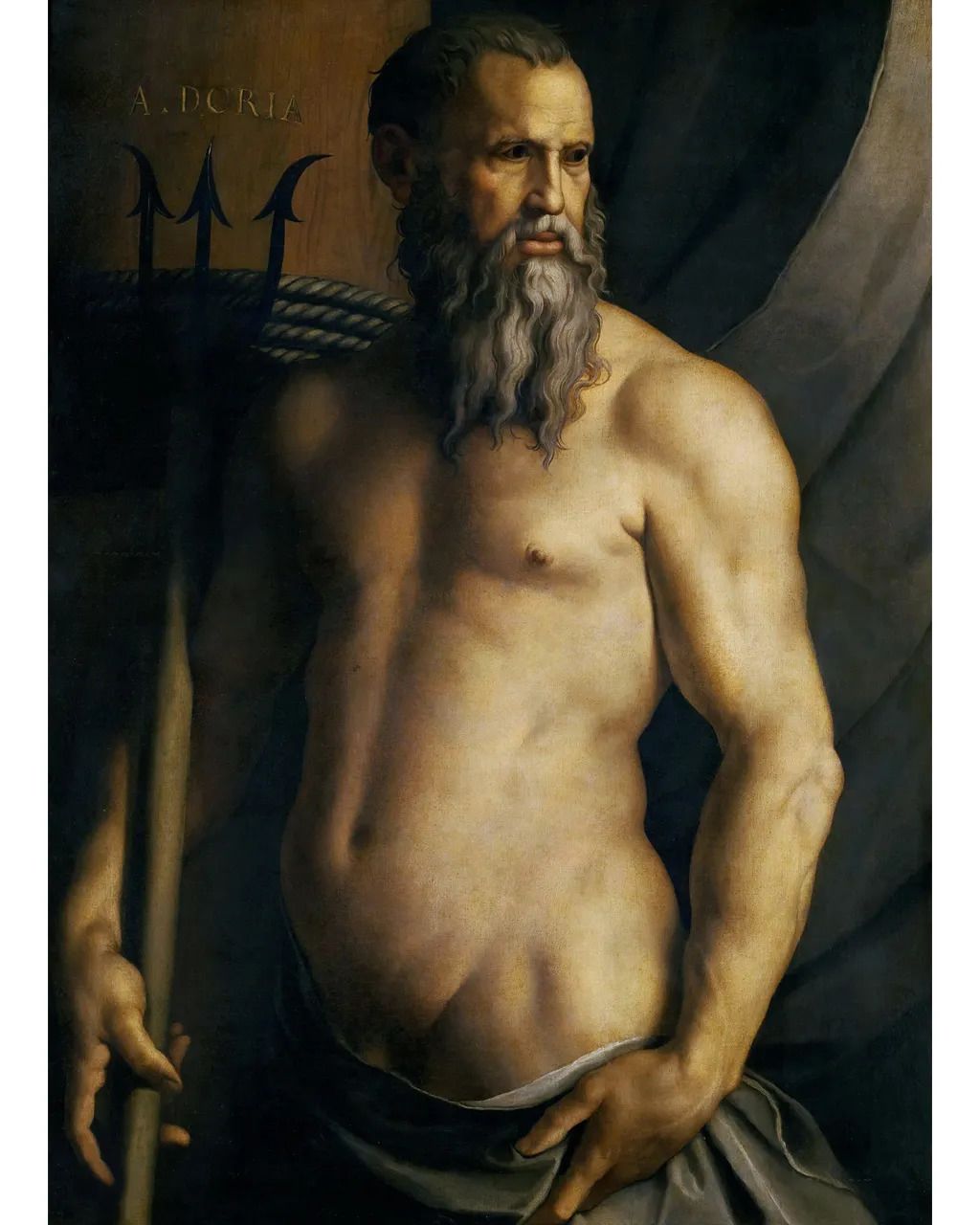

In Bronzino's 1530 portrait of the admiral Andrea Doria, his subject

chose to be depicted in the mostly-naked, muscular form of the sea god

Neptune

In Bronzino's 1530 portrait of the admiral Andrea Doria, his subject

chose to be depicted in the mostly-naked, muscular form of the sea god

Neptune

"Sending nudes" is more of a live topic than ever, chiefly because the ease of taking, replicating and sharing naked images has led to anxieties about everything from revenge porn to celebrity sex tapes, hacked private images to sexting teenagers. But since the advent of smartphones, sending nudes has also become normalised incredibly quickly: any woman who's been on a dating app in the last decade will likely have been asked to share nude pictures with eyebrow-lifting speed.

But Ingles reminds me that sending nudes isn't really new: "When I was in my early twenties, I sent nudes to someone – this was before the internet, so it was Polaroids". It's just that it used to be a private, little-spoken-of activity, rather than part and parcel of digital dating and contemporary life.

Its increasing prevalence as a phenomenon is neither a simply "good" or "bad" thing, Ingles – and the writers of Sending Nudes – suggest. While the potential for coercion, abuse and shaming are high, sexting can be a fun, consensual way to develop intimacy. During a pandemic, it's also become almost a practical necessity for many – a way of keeping sexual fire alive, over enforced distance.

The artworks of our era?

Arguably, there are also positives to having a greater openness and diminished prudishness about real-life, normal human bodies. But then, few people sending nudes traffic in realism. Seductive nude selfies are usually staged and carefully framed, albeit often within the confines of a bedroom or bathroom; dressed up for as well as undressed for. Posed and carefully lit, cropped and filtered to flatter, they are crafted for the imagined appreciation of the viewer. In that way, are nude selfies part of a lineage of naked representation that runs back through art history?

Certainly, you could argue the selfie – including the naked one – is the artwork of our time. It's estimated that over a million selfies are taken every day: self-portraiture meets self-promotion. We're more aware than ever not only of our own image, but our presentation of it – how we make ourselves appear to the eyes of the external spectator. And nowhere is that more carefully manipulated, surely, than in the nude snap.

The art world is increasingly taking note of the selfie form. In 2017, Saatchi Gallery in London opened a show, From Selfie to Self-Expression, drawing the line between traditional self-portraits through to the humble camera phone shot, from Rembrandt and Van Gogh through to Kim Kardashian and Barack Obama. "Everything can be art if it's followed through by the maker with enough conviction and coherence," commented Nigel Hurst, CEO of Saatchi Gallery. "We're not saying that the slideshow of a teenager trying out various poses is as significant as a work by Rembrandt, but the art world cannot ignore this phenomenon."

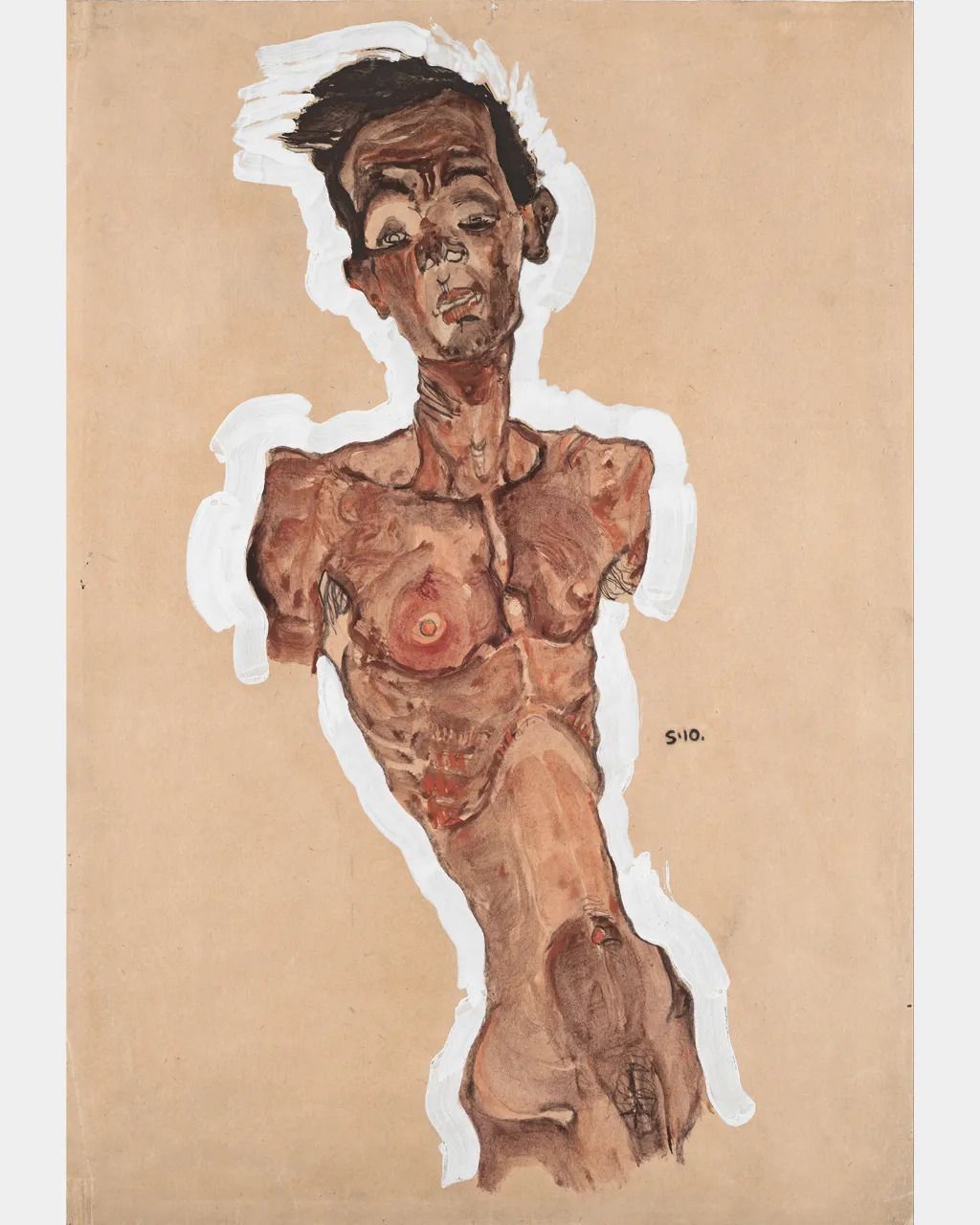

Egon

Schiele was among the artists who in the early 20th Century turned

their gaze on their own bodies – though their depictions were rarely

flattering

That same year, the Sexting Art Festival was held at the Littlefield Gallery in Brooklyn. The organisers wanted to redress the lack of conversation, analysis or display of the "wide spectrum of work" that constitutes sexting, by showcasing it in all its forms, visual and otherwise.

Meanwhile in 2016, the National Portrait Gallery had a show called Exposed: The Naked Portrait, which revealed just how acceptable – fashionable, even – it's become for celebrities to strip off for their own professional "selfies" – "revealing" and "honest" photographic portraits by the likes of Annie Leibovitz, David Bailey, Norman Parkinson, Mario Testino, and Polly Borland.

From buxom fertility goddesses through to heroic Greek gods, the unclothed human body has been recreated from the moment we could carve rock

The pervasiveness of the "nude selfie" is just the latest step in our ever-evolving relationship with the naked image. From buxom fertility goddesses through to heroic Greek gods, the unclothed human body has been recreated from the moment we could carve rock.

While it was the muscular, well-proportioned male form that was celebrated in Ancient Greece, once we came to the Renaissance, the focus began to shift to women. Hunky, idealised nude male figures from myth or the Bible still occupied artists' imaginations (think of Michelangelo's David, or depictions of Adam) – but a new fondness emerged for the reclining female nude.

Artists rendered the nude "respectable" in various ways: they painted goddesses or biblical figures as anonymous, generalised images of "beauty", rather than portraits of specific or identifiable women. Painted in supposedly modest poses with hands delicately placed to notionally conceal their genitals, they also trafficked in idealism, not reality: no pubic hair here.

But rarefied and legitimised as they might be, such nudes also – inevitably – carry an erotic charge. These supine naked women invite the eyes of the – imagined male – viewer to travel all over their curves. Many entrenched ideas of what feminine sexuality looks like – a certain languorous passivity, simultaneously coy and come-hither – are codified here.

The first "nude selfie" by a female artist is thought to be Paula

Modersohn-Becker's Self-Portrait Nude with Amber necklace (1906)

The first "nude selfie" by a female artist is thought to be Paula

Modersohn-Becker's Self-Portrait Nude with Amber necklace (1906)

Of course, the erotic intent of nudes before the 20th Century was almost always that conjured by male painters catering to wealthy male buyers. In the art critic John Berger's hugely influential 1972 essay Ways of Seeing, he argued that, historically, "Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at… The surveyor of woman is herself male: the surveyed female. Thus she turns herself into an object – and most particularly an object of vision: a sight." He proves this via examination of the frontal female nude in European art: the female subject, painted by a male artist, offering themselves up and out as an object, to be looked at by heterosexual men. For hundreds of years, women were only able to see external representations of their gender filtered through a male gaze, and therefore internalised that way of looking at themselves too.

Nudes with agency

I asked Frances Borzello, art historian and author of The Naked Nude, if there are any examples of pre-20th Century nudes expressing women's agency – for example, portraits commissioned by a wife or mistress of themselves in order to please or tantalise a partner or lover? "I don't know," she says. "They would hardly advertise this though one assumes it must have happened – occasionally!"

She brings up Goya's La Maja desnuda: a famously frank nude, who unabashedly eyeballs the viewer. Not that the model commissioned or owned her own image – it's thought the painting was made for a man's private collection of nudes – but art historians have speculated that it is at least an explicit, realistic portrait of one specific and willing female subject, who might have been Goya's lover. "The striking features are the opposite of the bland and often hazy features of the ideal nude," Borzello says.

Artists turned their gaze on their own bodies, though they rarely recreated them in flattering or well-mannered images

In terms of self-promotion, commissioned portraits of the wealthy and powerful were usually, for reasons of respectability, fully clothed – both men and women – but there are rare exceptions. These include a wonderfully eccentric 1530 portrait of the admiral Andrea Doria, painted by Agnolo Bronzino as Neptune, complete with trident and naked torso; and a 1670 painting of Nell Gwyn, an actress and also King Charles II's mistress, in which she is posing topless.

But it is at the start of the 20th Century when the naked self-portrait exploded in popularity. In this period of great artistic and intellectual change, artists turned their gaze on their own bodies, though they rarely recreated them in flattering or well-mannered images. Anguished mental states seem to thrum off the canvases, as in the harsh, blue-toned naked self-portraits of Richard Gerstl, the scowling, disturbing contortions of Egon Schiele, or when Edvard Munch painted himself "in Hell", his haunted face surrounded by flames.

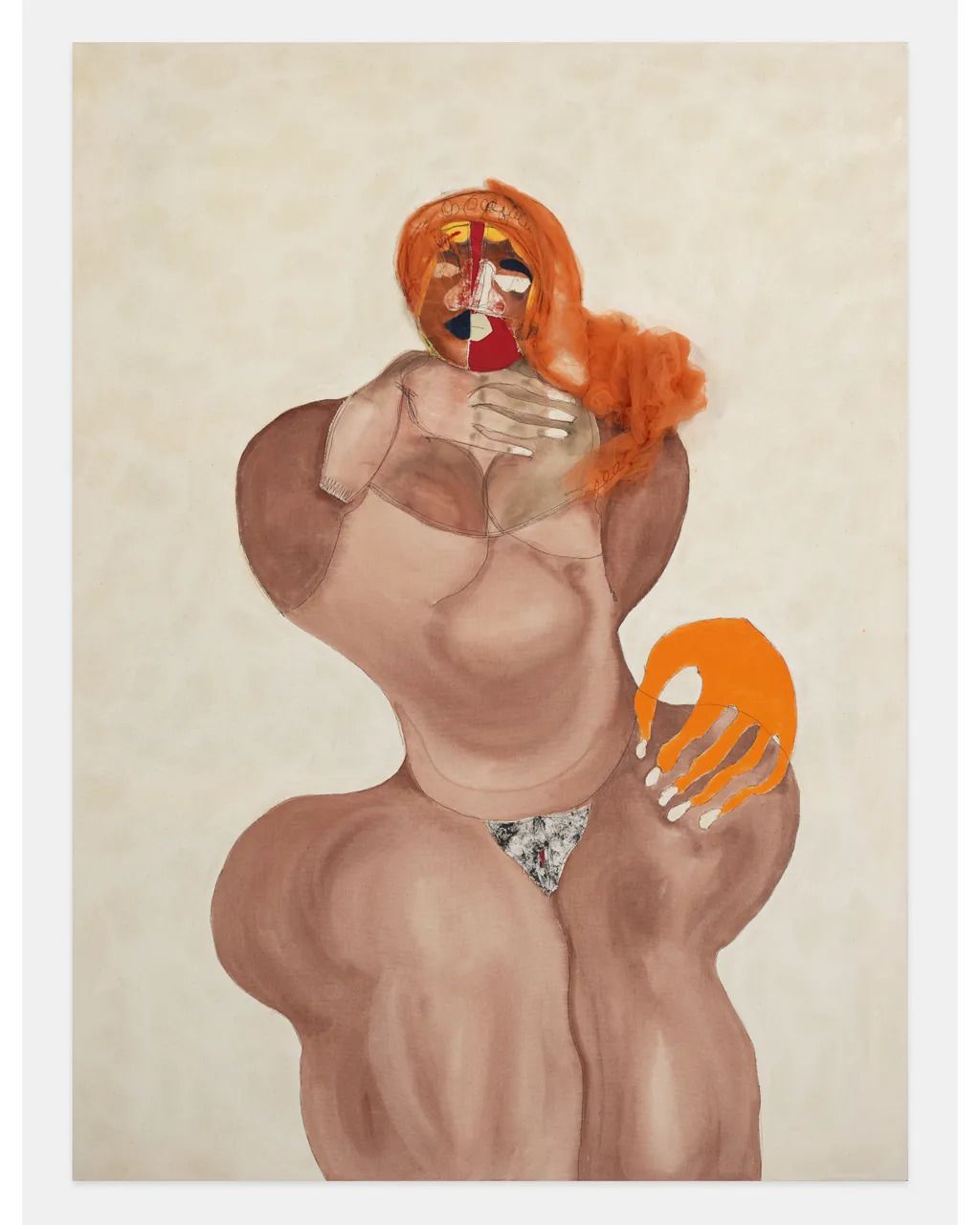

Tschabalala Self's erotic mixed-media collages bear a selfie-like aesthetic

Tschabalala Self's erotic mixed-media collages bear a selfie-like aesthetic

All these naked self-portraits were painted within the first decade of the 20th Century – and rather set the tone for the rest of it. Such paintings were possible, writes Borzello in The Naked Nude, because these artists had "no-one to answer to but themselves… These naked portraits follow no tradition. They are new. They make the private public. And they left a legacy."

Modernism continued to effectively kill off the idealised reclining nude, as messier, more complicated images of naked bodies proliferated. Both in artists' naked self-portraits and in nude portraits of others, a concern with the body's less-than-picturesque aspects remained ascendant – from Picasso's shattered forms to Lucian Freud's lumpy flesh.

How women reclaimed their image

But the story of the 20th Century nude is also the story of women, finally able to paint themselves. The first "nude selfie" by a female artist is thought to be Paula Modersohn-Becker's Self-Portrait Nude with Amber necklace, in 1906, where she paints herself pregnant, despite not being so. It's an imaginative take that's about female identity – not the male gaze.

For many female artists, creating their own take on the nude becomes a way to reclaim the stereotyped image of woman from the masculine traditions of Western art history. Florine Stettheimer's 1915 A Model (Nude Self-Portrait) cocks a snook at the traditional reclining nude: Stettheimer paints herself with a knowing smile, proffering her own colourful bunch of flowers like a magician's trick – an active riposte to Edouard Manet's infamous, unimpressed-looking 1863 nude, Olympia, which features a white sex worker being brought flowers from a suitor by a black servant.

Whether in advertising, pop culture, or pornography, the naked body has become defined by its attractiveness as a monetisable object.

For women, as much as for men – perhaps even more so, given they were actively trying to counter hundreds of years of artistic airbrushing of their bodies – naked self-portraits became concerned with conveying uncomfortable truths about what it is to have a body. From Frida Kahlo's symbol-laden portrait of her own miscarriage to Jenny Saville's close-up rolls of flesh and Tracey Emin's scratchy masturbation paintings, the "nude selfie" became truly unfiltered.

But if the pendulum swung away from the notion of the idealised nude in Western culture, it eventually swung back, albeit in a new form. Whether in advertising, pop culture, or pornography, the naked body has become defined by its attractiveness as a monetisable object. And that's a paradigm that has been picked apart by Pop Art, post modernism, and beyond. In general, contemporary art is more likely to use an idealised naked body to critique attitudes towards sex, pornography and consumption than it is to plainly ape them – although viewers of, say, Jeff Koons' super-glossy soft-core staged photographs with his then wife, adult film star Ilona Staller (aka La Cicciolina), might be forgiven for feeling otherwise.

Erin M. Riley's tapestries explicitly recreate nude selfies, based on real images she finds online

Erin M. Riley's tapestries explicitly recreate nude selfies, based on real images she finds online

However some nude images channelled eroticism in a way that was truly radical. Consider Robert Mapplethorpe's black and white photographs of naked gay men, including himself, engaged in BDSM and sex acts, which caused such a furore that Washington DC's Corcoran Gallery cancelled a show of them in 1989. Then, bringing such kink into the light was shocking; today, the controversy has dimmed, and Mapplethorpe is subject to major, respectable retrospectives.

The language of the smartphone nude

When it comes to the advent of the smartphone-facilitated nude selfie, meanwhile, the question is: how have we absorbed this language and grammar of nakedness? It's something that artists are certainly exploring, recreating the camera angles, the up-close poses and pouts, the partially-pulled-down underwear on gallery walls.

Ghada Amer embroiders works that, beneath their fine surfaces, recreate the codified poses – the hand on the stuck-out bum, the coyly pulled-down bra strap, the over the-shoulder inviting look – of the nude selfie. Tschabalala Self's mixed-media collages stitch together exaggerated images of black female bodies that speak to the way they can be both sexually empowered, and crudely sexualised, in contemporary visual culture. "The fantasies and attitudes surrounding the black female body are both accepted and rejected within my practice,” she has said. Erin M Riley's work explicitly recreates nude selfies – but immortalises them within tapestries. Based on real images she finds online, she includes details like a mobile phone reflected in a mirror or the familiar hand-held camera angle, looking down the body.

Some artists have gone further, literally using other people's Instagram posts. David Trullo turned Instagram posts of men photographing themselves nearly-nude in bathroom mirrors into bathroom tiles. Meanwhile, for his New Portraits series, controversial painter/photographer Richard Prince left suggestive replies below people's Instagram selfies, often those of young women and sexily posed (if not fully-naked), then blew up and printed out the posts. But if the series was intended as some kind of satirical comment on how we're all obsessed with crafting our own attractive self-images – and giving them away for free to anyone who cares to look – then that was mostly obscured by his co-opting and profiteering from women's images without their consent.

One subject, Zoë Ligon, told ArtNet that she thought the work "resembles revenge porn and harassment more than anything else"; explaining that she was a survivor of childhood sexual abuse and her "sexy selfies" were a way of reclaiming her sexualised image, she said she felt "violated" by Prince's use of one. The issue of his appropriating women's pictures was brought into wider consciousness when model Emily Ratajkowski wrote about buying one of Prince's works using a post from her Instagram, within a potent, widely-shared piece about not having control over her own image last year.

Absolutely, I think the nude selfie can be an art form. It’s nice to see that thought and reflection. It shows the person respects themselves – Julianne Ingles

While Prince's work inadvertently highlights very serious questions about how the selfie can be appropriated unethically, it is also clear that it is a medium which deserves artistic interrogation. Here is a striking, thorny new form of communication and self-presentation – and one that is, after all, purely visual. Nonetheless, in transposing that visual language into a new medium or context, artists are both reflecting on and actively removing the primary function of the private nude: they are not seeking to turn the viewer on. "I honestly don't know of artists who would admit to intentionally titillating," says Borzello.

In his work, David Trullo has turned Instagram posts of men

photographing themselves nearly-nude in bathroom mirrors into bathroom

tiles

In his work, David Trullo has turned Instagram posts of men

photographing themselves nearly-nude in bathroom mirrors into bathroom

tiles

But does the nude selfie, in its purest state, have the potential to be a new art form? Ingles thinks so. "Absolutely, I think that it can be an art form," she says. "It's nice to see that thought and reflection, not just snapping a photo – people taking time to do the lighting, your hair and make-up. It shows the person respects themselves."

Which brings us back to Berger's formulation of how, when a woman imagines themselves through the eyes of the external, male viewer, she "turns herself into an object… of vision: a sight." Fifty years on, women are still more judged on how they look than men, and the tyranny of that internalised male gaze persists. But it also seems that anyone engaged with visual digital culture – anyone posting selfies and in particular anyone sending nudes – is today actively participating in turning themselves into an object of vision.

The irony is, perhaps, that the filtered, posed, explicit images we now so easily recognise as a smartphone nude might have come full circle – bringing us back to the aesthetic of the traditional respectable art historical nude: codified, safe and strangely conventional. Designed to be gazed upon. Designed to please the viewer. Designed to turn our complicated and messy bodies into the ideal object.