Hong Kong Family’s $3 Billion Buyout Windfall Keeps Paying Off

The biggest decision of the 42-year-old scion’s career is now looking savvier than ever.

Woo’s buyout of Wheelock & Co. not only lifted the valuation of a company that had long been saddled with a conglomerate discount, it also shifted the clan’s holdings toward the resilient residential real estate sector. The buyout was funded in part by family stakes in companies with exposure to retail and commercial properties, which have suffered far more from the pandemic and Hong Kong’s anti-government protests.

It may be the start of a broader push by Woo to re-orient his family’s fortune, according to Peng Qian, an associate director of the Tanoto Center for Asian Family Business and Entrepreneurship Studies at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. The family’s net worth was valued at $20.2 billion in this year’s Bloomberg Billionaires Index list of Asia’s richest dynasties, up $3.5 billion from a July 2019 ranking.

“The privatization will help the family restructure their businesses and diversify into different assets in the future,” said Peng, who speaks with Woo at family-office events in Hong Kong, though isn’t privy to any specific plans for Wheelock.

While few expect the Woos to end their focus on the world’s priciest real estate market, the buyout has made it easier to tweak the business by freeing the family from scrutiny of minority shareholders. It’s one of at least $26 billion in privatization transactions announced by controlling families and other related parties globally this year.

It wouldn’t be the first time Woo’s clan has pursued a strategic shift. His maternal grandfather, Pao Yue-kong, made his first fortune in the shipping industry. Known as the “Ship King” in Hong Kong, he once controlled the world’s largest independently owned bulk-shipping fleet.

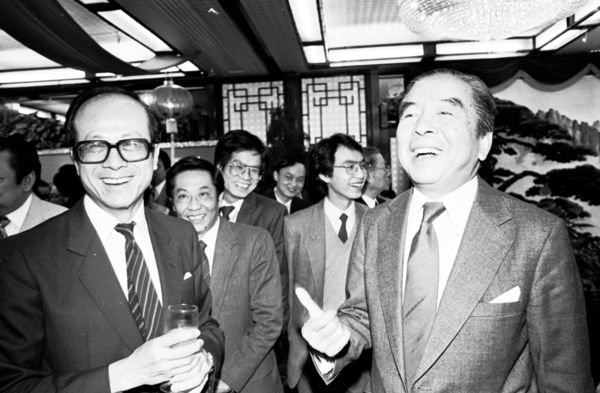

Pao made the leap to property in the late 1970s by buying a 10% stake in Hongkong and Kowloon Wharf and Godown Co. from Li Ka-shing, now the city’s richest man. Woo’s father, Peter, who is married to Pao’s second daughter, eventually took over. He handed the reins to Douglas, a Princeton and UBS Group AG alum, in 2014.

“The family has shown a strong ability to adapt to global trends,” said Hao Gao, director of Tsinghua University’s NIFR Global Family Business Research Center.

Unlike his father, who unsuccessfully campaigned to become Hong Kong’s first chief executive right before the city’s 1997 handover to China from Britain, the younger Woo has shunned publicity. He’s never given a media interview outside usual appearances at company news conferences. A press representative declined to comment for this story.

Woo’s low profile hasn’t stopped him from making a big mark on the family business. The take-private deal, which offered a 52% premium and triggered a 40% surge in Wheelock’s stock the day it was announced, looks particularly well-timed in hindsight, said Patrick Wong, an analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence.

It was financed with a mix of cash and some Wheelock shares in two other listed units that focus primarily on retail and office properties. After the buyout, Wheelock’s stakes in those businesses -- Wharf Holdings Ltd. and Wharf Real Estate Investment Co. –- dropped to around 50% from 70%.

Wheelock’s other holdings are comprised mostly of residential developments and land. The family ended up paying about HK$8 billion ($1 billion) in cash to get full ownership of residential land banks that could be worth HK$100 billion, Wong said.

Hong Kong’s residential property market has remained remarkably resilient this year. Prices for homes have edged up slightly, while those for offices and retail space have dropped more than 6% and 2%, respectively, according to the latest available data from the city’s Rating and Valuation Department.

Skeptics say it’s only a matter of time before the housing prices tumble, given that Hong Kong is mired in its deepest-ever recession and a growing number of residents is looking to escape China’s tightening grip on the city.

Still, Wheelock and plenty of other market insiders have expressed optimism about the long-term outlook. One potential catalyst for further gains: China’s plan to make Hong Kong a pivotal piece of the Greater Bay Area project -- an attempt to build a Silicon Valley-like cluster of technology and financial hubs along the country’s southern coast.

Wheelock has the second-largest residential land bank in Hong Kong, trailing only Sun Hung Kai Properties Ltd. The former’s luxury residences in Kai Tak, a new development on the site of the city’s old airport, could fetch about HK$25,000 a square foot, according to Bloomberg Intelligence. That’s 60% more than the average in Hong Kong and triple the mean in Paris, data compiled by CBRE Group Inc. show.

Kai Tak is where Wheelock will focus in the future, according to a company presentation in March. It has acquired five sites there, including a HK$6.9 billion parcel in February 2019 from debt-laden conglomerate HNA Group Co., to build luxury homes next to the city’s planned second business district. The developer launched its first project in the area last year and has seven others under construction.

“The new structure offers flexibility for the Woos,” said Jeremy Cheng, a researcher at the Center for Family Business of the Chinese University of Hong Kong. “The prior social movement and the current pandemic may have raised the tendency for them to conduct a more frequent set of reviews and strategic realignment. Families need to be more agile.”