Gas prices, interest rates, NHS waiting lists - charts reveal what may happen in 2023 I Ed Conway

Still, that needn't stop us having a shot, so without further ado, here are some of the charts that might help tell the story of 2023.

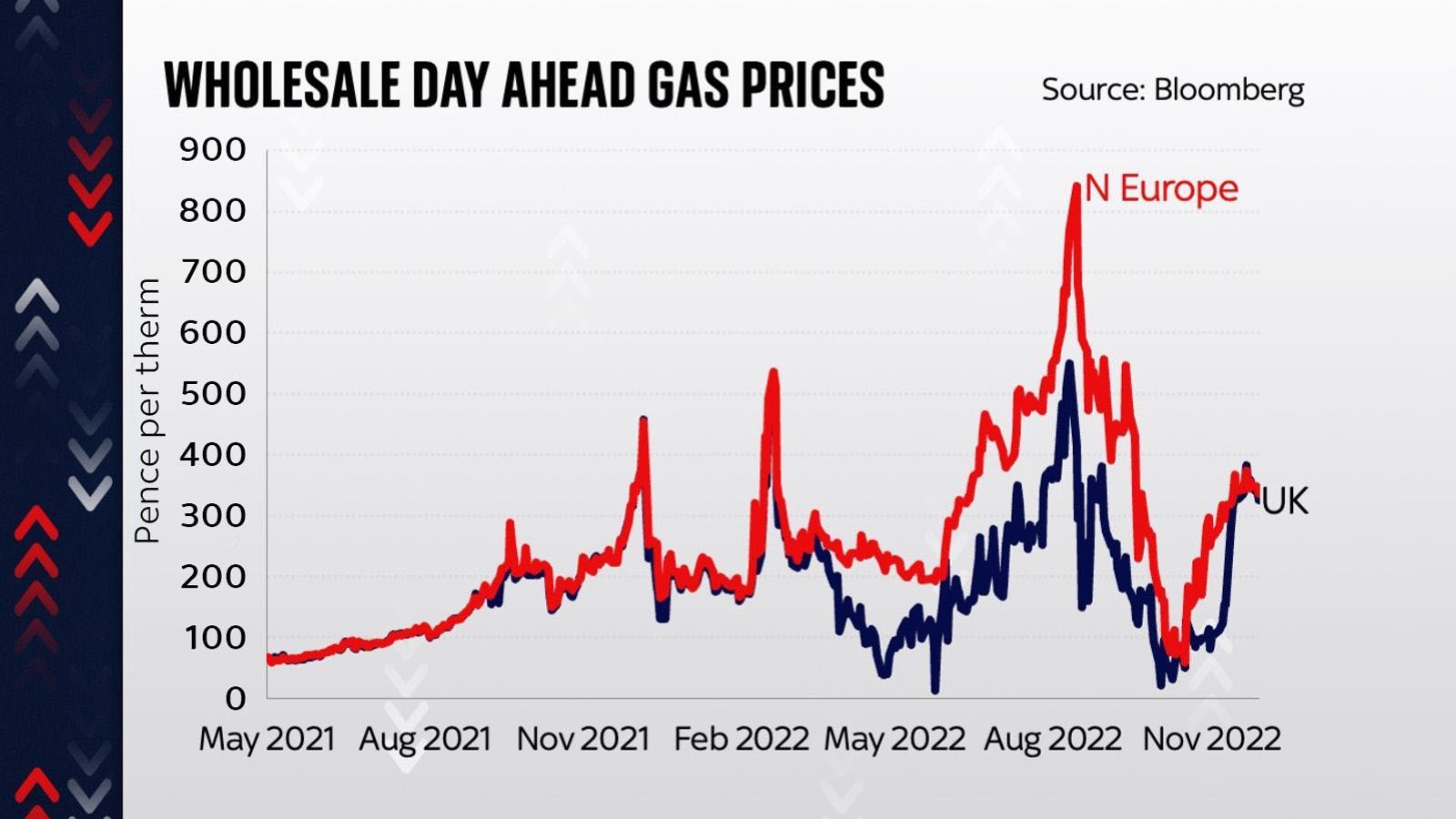

1. The gas divergence

One of the most curious things about 2022 was that even as it faced a serious gas price spike, the UK was awash with natural gas. This was in large part a consequence of the industrial geography of the gas market, where prices and flows are in large part a consequence not just of supply and demand but of something far simpler: where the pipes are and where the gas comes in.

The UK typically tends to send gas across the pipelines running over the channel into the continent during the summer and sucks it back in the winter. The reason it was drowning in gas even as we faced a so-called "shortage" earlier in 2022 was that at that point, Europe was crying out for extra gas and one of the only places to get it was via big liquefied natural gas carriers, most of which had to dock in the UK before sending their cargo through British pipelines over to Europe to be stored.

There are a couple of interesting points here. First, the UK played quite an important role in helping provide gas throughout for Europe to fill up its storage. But the other consequence was to cause a big gap between UK and European gas prices.

Much will depend on how quickly Europe can build its new terminals to suck in extra gas, but the important consequence of all this is clear. These wholesale prices influence the prices we all pay for our gas bills. The gas market's strange peccadilloes never mattered all that much before last year. All of a sudden they're all important.

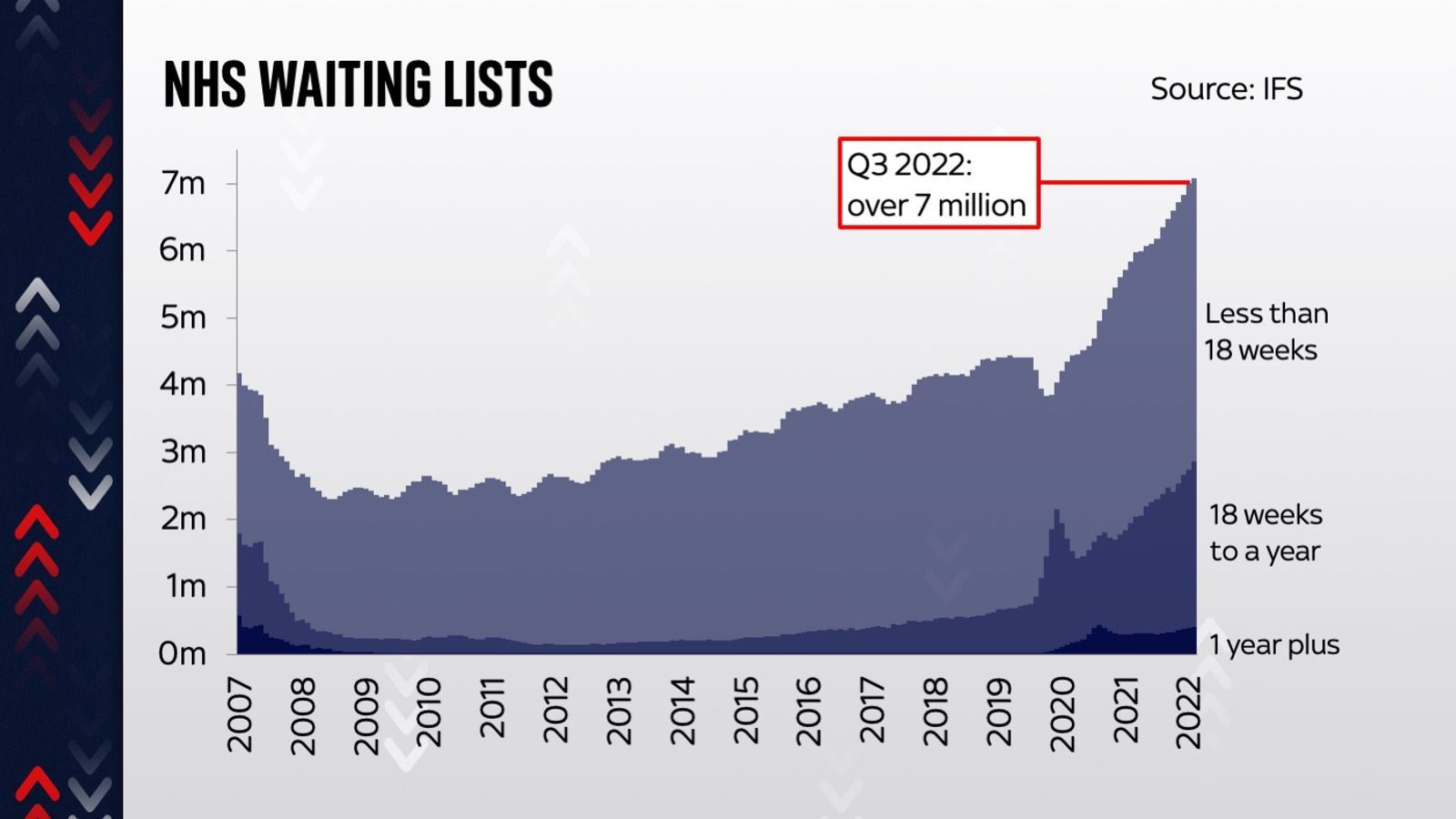

2. The ever-growing waiting lists

One of the defining features of 2022 was the swelling ranks of people on NHS waiting lists, which mounted, all told, to over 7 million by the latter half of the year. The big question is how quickly the NHS will be able to clear these backlogs.

The likeliest prospect is that these numbers carry on rising this year and do not peak until 2024, making this another tough 12 months for the NHS. The problem is that not only is it trying to deal with the increasing burden of an ageing and less healthy population and the growing cost of pharmaceuticals, it is also facing this enormous overhang from the COVID period. Oh and this is before one considers the impact from the industrial action over the winter. In short, if you thought 2023 might be the year the NHS would disappear from the headlines, think again.

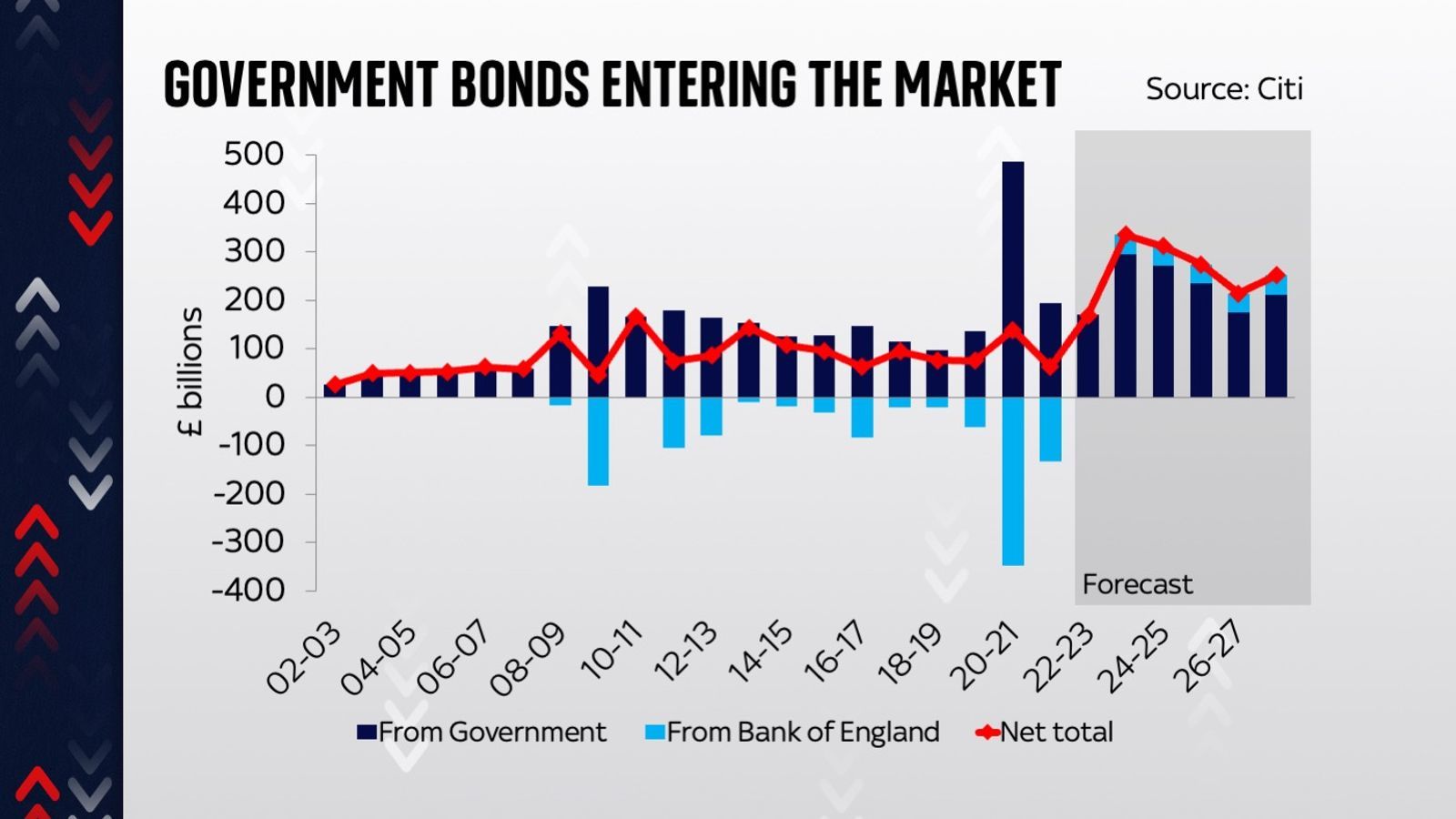

3. A tidal wave of bonds

This chart is quite complex but once you get your head around it it's pretty astounding. The back story here is that the government bond market, once upon a time one of the most boring corners of the financial system, became very exciting in 2022 following the mini-budget and it might continue to be exciting (and not in a good way) in 2023.

The overarching point here is that this market, where the government auctions bonds (IOUs - sometimes called gilts) in order to raise money, is facing a potential spate of indigestion.

The bars are showing you the amount of UK government debt entering the market in the coming months. Anything above the line is money being sold to private investors. Anything below the line is bonds being bought off private investors.

And you can see a few things emerging here. Look first of all at the dark blue lines. That's debt being issued by the UK government - it's all those bonds they auction to finance much of their spending (remember they still borrow a lot more than they raise in taxes). You can see a few big peaks in bond issuance: around the 2008 crisis and recession and then again in 2020 when COVID struck. It's the flip side of saying there were big deficits those years.

But there's something else going on too. Look at the light blue bars. These are the bonds the Bank of England is buying/selling. And you can see how, through its quantitative easing (QE) programme it was buying up LOTS of government bonds in years gone by. That 2020 splurge of debt by the government was almost entirely "cancelled out" by the fact that the Bank of England was simultaneously buying hundreds of billions of pounds of bonds off investors via its QE scheme.

Now roll onto 2023 and because the Bank of England is no longer buying up those bonds from investors but reversing quantitative easing and selling them, the light blue bars are now above the line. The upshot is that the private sector is being asked to absorb an unprecedented amount of government debt. The red line - which nets out the blue bars - is the one that matters here. It's higher than ever before in the coming years. No one knows how easily the market will digest that debt but we're about to find out. It could be a bumpy ride.

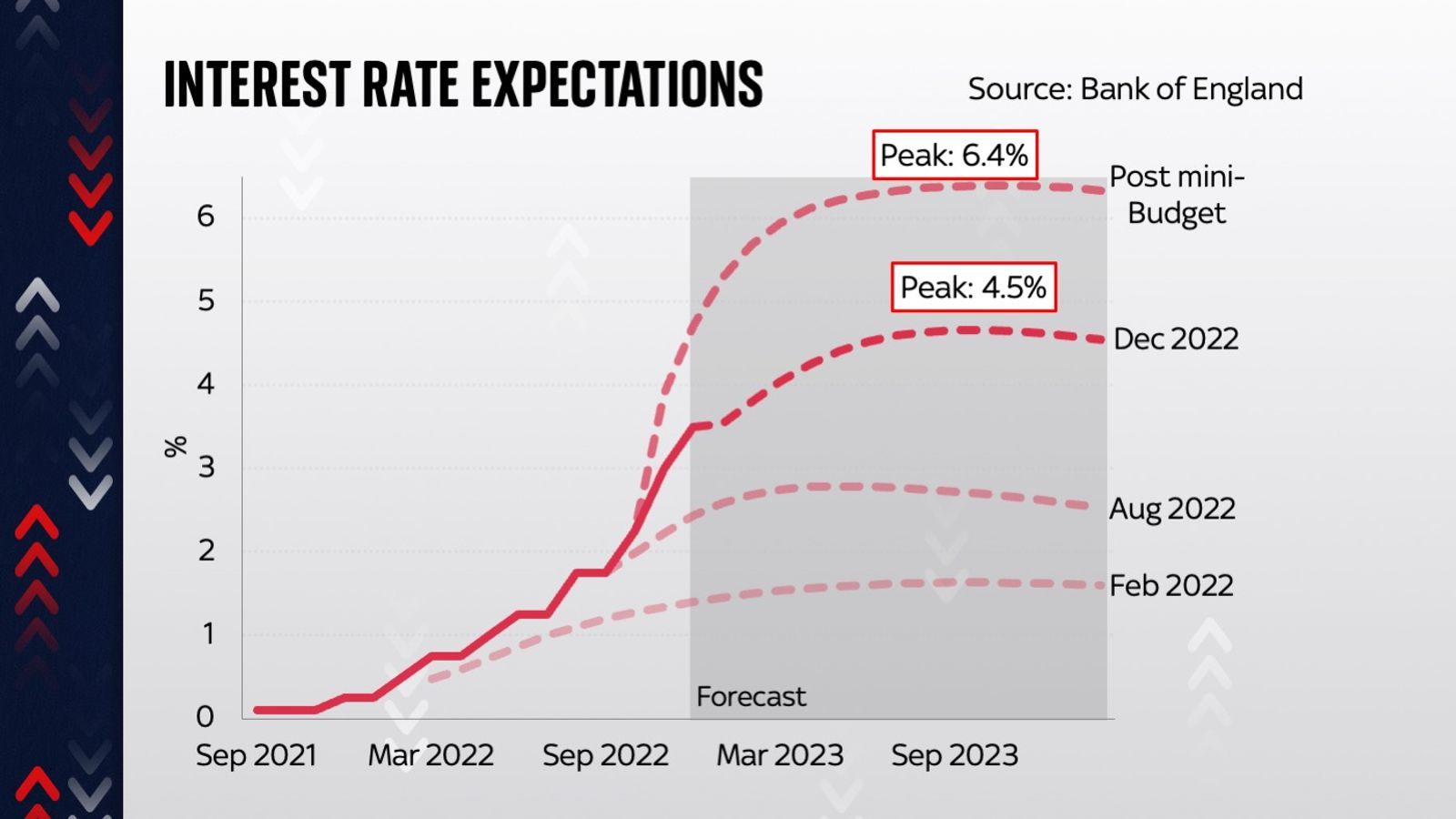

4. Interest rates

For many households, this is the main chart that matters this year. We became quite used, over the past few years, to interest rates at rock bottom levels. But that has begun to change. The only question now is how high those rates get.

While it's hard to know for sure where they'll end up (just as it's hard to know what Vladimir Putin is planning next) the market has some guesses. But what's striking is how much those guesses have evolved in recent years.

Think about it. Less than a year ago traders in money markets were still expecting that rates would rise no higher than about 1.5% in the coming years. That of course began to change as the year wore on, a combination both of rising inflation and of the change in government in the UK. Even so, what happened after the mini-budget was quite extraordinary: the expected peak rose from around 4.5% to as high as 6.4%.

Now, the Truss government didn't last long and the rates dropped back thereafter. All the same, money markets still expect interest rates to get to 4.5% by the middle of next year. The question, then, is whether this turns out to be right, or whether the Bank stops short of this, as it has frequently hinted it would. The other question is whether rates begin to fall quickly thereafter.

The consequence for many households, however, is that the cost of borrowing, for a decade or so something they rarely had to think that much about, will be considerably higher. Mortgage misery - the subject of many discussions in the 1990s - will be back again. On the one hand, a sizeable number of older households are now lucky enough to have paid off their mortgages. On the other hand, for those who have mortgages (or for that matter those renting) property costs are only going in one direction. In much the same way as the cost of living dominated 2022, this is very likely to be one of the stories of 2023.