Dozens of English care homes lost at least 20 residents to Covid, data shows

Dozens of care homes in England lost at least 20 residents to Covid-19 during the pandemic, according to “highly sensitive” data published by the care regulator, with one home registering 44 deaths over the past year.

The Care Quality Commission (CQC) revealed that 6,765 homes across the country registered at least one death between 10 April 2020 and 31 March 2021, highlighting the devastating impact of the crisis on vulnerable residents.

At least 30 deaths were reported by 21 homes. There were 44 deaths at the Bedford care home in Wigan, owned by the large private care home operator Advinia, and 41 deaths registered by Calway House in Taunton, owned by Somerset Care, a not-for-profit operator.

The CQC had refused to publish the death rates data for almost a year, despite pressure from residents’ families and freedom of information requests from journalists, on the grounds that it would undermine confidence in the already fragile predominantly privately owned residential care home market.

In total, there were 39,017 care home deaths over the period, prompting renewed criticism of the government’s failure to stem the outbreak in the residential care sector, and its failure to tackle years of underfunding and understaffing.

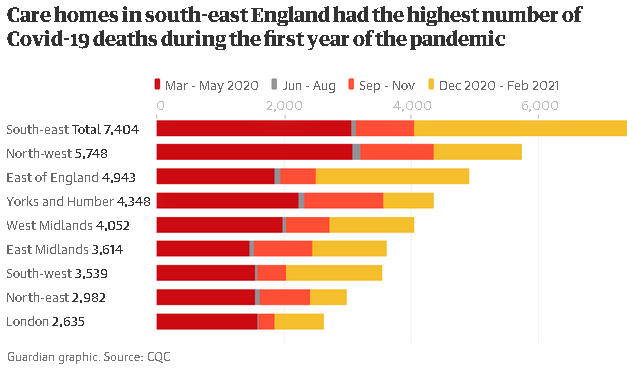

The highest number of care home deaths over the period were registered in the south-east region of England (7,404), followed by the north-west (5,748) and the east of England (4,943). The fewest deaths were recorded in London (2,635).

“In considering this data, it is important to remember that every number represents a life lost – and families, friends and those who cared for them who are having to face the sadness and consequences of their death,” said Kate Terroni, the CQC’s chief inspector of adult social care.

In a statement, the CQC suggested its about-turn on publishing the data came partly following discussions with families who had lost loved ones to Covid. This “helped us shape our thinking around the highly sensitive issue of publishing information” around death notifications on a home-by-home basis.

“We have a duty to be transparent and to act in the public interest, and we made a commitment to publish data at this level, but only once we felt able to do so as accurately and safely as possible given the complexity and sensitivity of the data,” said Terroni.

However, the CQC warned the data should be treated with caution because they were not a reliable guide to care quality or safety at individual care homes. Homes are required to register the death of residents even if they died in hospital or contracted the virus elsewhere.

There are currently around 15,000 care homes inspected by the CQC. Other factors potentially leading to high death rates include the the prevalence of Covid infections in the local community, the availability of PPE, and the number of residents who were discharged from hospital to homes without being tested for the virus during the early phase of the pandemic.

Around 25,000 people were allowed to return to care homes without a Covid test between 17 March and 15 April last year despite a plea to the government from home providers to outlaw the practice. This is believed to have enabled the virus to spread rapidly through homes populated with older, vulnerable residents.

Care home owners were said to be unhappy about the publication of the data because of the danger of it being misinterpreted. Martin Green, chief executive of Care England, which represents care providers, said every death needed to be seen in context. “We do not believe that this data is a reflection of quality.”

A Department of Health and Social Care spokesperson insisted the government had done all it could to protect protect vulnerable people throughout the pandemic, saying: “We have provided billions of pounds to support the sector, including on infection and prevention control measures, free PPE, priority vaccinations and additional testing.”

James White, head of public affairs and campaigns at the Alzheimer’s Society, said the data showed the “devastating and tragic consequences” of the government’s failure to protect care homes at the start of the pandemic, and the damage caused by years of underfunding.

Hugh Alderwick, head of policy at the Health Foundation, said the CQC data showed how government support for social care during the pandemic was often “too little, too late”, particularly during the first wave. “The government’s claim of ‘a protective ring’ around care homes was not grounded in reality.”