Chris Mason: Asylum backlog is complex issue to resolve

Before the Autumn Statement, the budget in all but name last month, I was told the prime minister was devoting more time to it than anything else but the statement.

Quite something, given the range of issues that cross a prime minister's desk.

The government is desperate to get a grip on what Home Secretary Suella Braverman has said has been a failure to control the UK's borders.

They want to cut the numbers crossing the Channel in small boats.

They want to deport asylum seekers whose claims are rejected much more quickly.

And they want to house asylum seekers whose cases are being worked on more cheaply.

Why?

Because they have concluded it's a big deal for millions of people, and, having candidly pointed out the failure of Conservative governments over the last 12 years to sort it out, or even adequately manage it, they now need to show they are up for it.

Let's be blunt: this is an incredibly difficult and complex issue to resolve, whatever resolution even means on this.

Take a look at this from more than 20 years ago, when Labour Home Secretary David Blunkett was promising a crackdown, including making the asylum process quicker.

Two decades later, Mr Sunak is promising exactly the same. How the issue presents itself varies.

Back then it was about the Red Cross refugee camp at Sangatte near Calais and migrants trying to cross by climbing into the back of lorries or get through the Channel Tunnel.

Now, it is small boats and a particular influx from Albania.

In a world where you're only a smartphone scroll away from knowing how rich some places are compared to home, let alone if you're also fleeing persecution, the lure of a country like the UK will always be there.

But let's unpack what the prime minister is promising.

Firstly, that issue that has dogged successive governments: making the asylum process quicker.

Mr Sunak said "we expect to abolish the backlog of initial asylum decisions by the end of next year". But when he said "abolish the backlog" he didn't mean all of the backlog.

Downing Street later acknowledged this meant making an initial decision in all cases that were outstanding at the end of June this year, when the system for processing cases was changed.

What happened at the end of June was the Nationality and Borders Act became law.

Since then it has been an offence to arrive on the shores of the UK without permission and so officials are now able to differentiate claims depending on whether people arrived through legal or illegal routes.

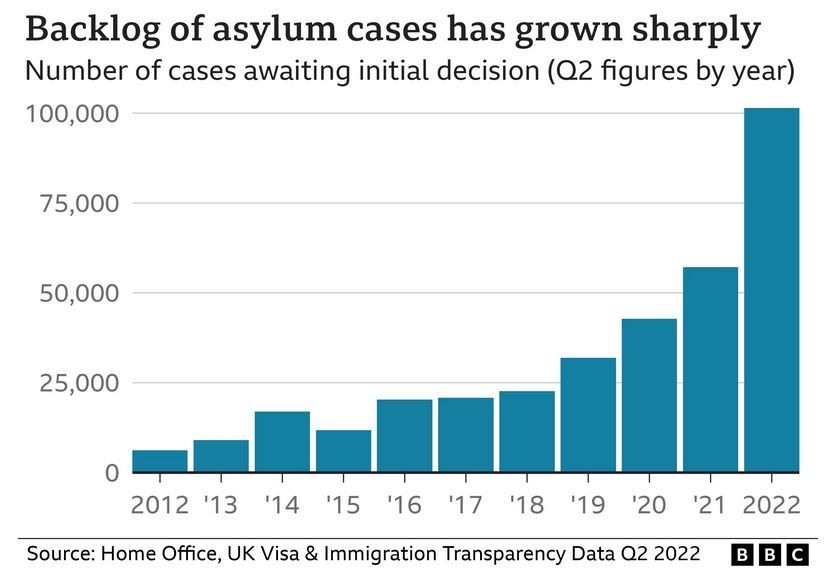

What ministers are actually committing to is clearing the backlog of 92,601 initial asylum decisions relating to cases made in June of this year or earlier.

As of September this year, there were around 117,000 unresolved asylum cases awaiting a decision, relating to around 143,000 people (a case can relate to more than one person because of families).

So that is around 24,000 cases that could still be unresolved in a year's time, on top of additional cases between now and then, that wouldn't count against the prime minister's definition of abolishing the backlog.

And as he acknowledged to me when I interviewed him, reaching an initial decision is often not the end of the matter, because people can appeal "and we're not in control of the pace of those appeals".

But what isn't clear is whether he would contemplate the UK leaving the European Convention on Human Rights, or be willing to ignore any adverse rulings from its court.

And one other thing in the package of ideas that caught my eye: the government's promise to cut in half the current cost of housing asylum seekers, often currently in hotels.

The current approach currently runs up a bill of £5.5m a day.

Instead, Mr Sunak wants people to be housed in disused military facilities, old holiday parks and former student digs.

But when I asked him where, he couldn't tell me, saying I wouldn't expect him "to comment on commercial negotiations".

I wouldn't - but if such negotiations are still ongoing, it's not nailed down that the necessary alternative accommodation will be available.

And that's before the huge political rows about the sites that are chosen, when there is a very good chance of strong local opposition.

So what about Labour's approach to all this, as they seek to present themselves as an alternative government?

Leader Sir Keir Starmer pointed to what he sees as persistent Tory failure on the issue, as well as what he called the "unworkable gimmicks" that ministers have suggested and remain committed to, such as deporting some asylum seekers to Rwanda.

But his response was notably short and he himself will want to appear robust on the issue, given how much it matters to so many people, particularly in seats Labour needs to win back to form a government.

This prime minister and his successors, whoever they are, will continue to wrestle with asylum and illegal immigration.

It's a challenge history suggests governments can only ever hope to manage, rather than solve.