Beautiful Portraits Show How Adoption Influences Asian American Identity

What defines your identity? Diana Albrecht, a Minneapolis-based photographer and art director, based her project Placed on this question. Over nearly two years, Albrecht connected with 10 Korean adoptees, many who had been raised in white families, to discuss how their identities were affected by their experiences. A lot of them spoke about their struggles to come to terms with their identities as people of color and their feelings of isolation from their Korean heritage.

“Community is not homogeneity but rather a conscious effort to use our diversity of lived experiences to build something more than ourselves,” Ben, one of the participants, told Albrecht. A self-described “moody romantic,” Albrecht said Placed was intensely personal — not only was she herself adopted, so were her father and brother. This made her keenly aware of the fluid space that people can inhabit between a sense of belonging and alienation, often influenced as much by a physical location as an emotional one. The project is a beautiful reminder of a community’s rich array of experiences, whether it’s as small as a family or as big as a nation.

Can you talk about what it means for you to identify as a Korean adoptee?

For me, to finally identify and wholly live as a Korean adoptee is getting rid of the shame I held towards my Asianness and finally forgiving myself for the multitude of ways I responded to that shame (i.e., assimilation, erasure of Asianness, internalized racism, etc.).

It's a grace I give myself, knowing I might never fully access the culture I came from; I can instead forge a community and culture unique to myself and the diverse experiences of other adoptees. Lastly, and most importantly, it’s an acknowledgement that while I am a woman of color, I have been afforded so many privileges due to my proximity to whiteness. I need to continue to hold myself accountable in dismantling the systems of oppression that tell us adoptees and other marginalized folks are less than.

How did you come up with this idea?

Three years ago, I found myself needing an escape from reality. So I retreated to a special place on a small island overlooking the Mississippi River. The secrecy, intimacy, and beauty of the environment allowed for a lot of introspection and healing. I wondered if a physical place [had ever] impacted others in a similar way.

Offhand comments from my dad (also a Korean adoptee) and brother (a biracial Asian American adoptee) made me question how people of color align to ideologies that do not support other people of color or even folks within their own diaspora. I wondered if our adoptions and, by default, our closeness to whiteness had something to do with this.

These two questions happened in tandem with each other and became the hypotheses that set the tone for Placed.

I chose to shoot the project on film because I wanted to be mindful of how each participant might feel meeting a stranger for the first time, opening up wounds and exposing vulnerabilities. Film allowed me to slow down, listen, and be even more thoughtful.

“What we are making is so much more about the sum of our parts, and our

physical expression is not just literal. So because of that, I wanted an

expansive space that is also intimate. It also is a theater that has

had so many different lives, and that was so attractive or, in

hindsight, biased, because I feel like as adoptees we feel that very

strongly.”

“What we are making is so much more about the sum of our parts, and our

physical expression is not just literal. So because of that, I wanted an

expansive space that is also intimate. It also is a theater that has

had so many different lives, and that was so attractive or, in

hindsight, biased, because I feel like as adoptees we feel that very

strongly.”  “For me, K-Town was my way of figuring out how I can appreciate the culture and still learn what it means to be Korean.”

“For me, K-Town was my way of figuring out how I can appreciate the culture and still learn what it means to be Korean.” Are there common themes you found among the people you met?

We’re all still trying to figure it out! That is a huge oversimplification of the adoptee journey, but there is not one participant who is at the finish line in this marathon. As the youngest adoptee featured in the book, I looked up to all the other participants, some of whom are 20 years my senior, and assumed they were at resolution with this whole thing.

In talking with some of the participants after the Atlanta shooting, which left six Asian women dead, we commiserated over the paralysis we felt in reacting to the tragic events. Some said they felt like they couldn’t connect with the AAPI community, because we as adoptees are so good at telling ourselves we are not Asian enough — and sometimes we receive that treatment from members of the AAPI community. Others felt like we weren’t allowed to complain about the rise of hate crimes against Asians in the past year because it would take away from the experiences of Black and brown folks.

Many of our white families and friends had not reached out to us, which left a lot of us feeling further confused and alone. While we’ve progressed so much in claiming our identities as Korean adoptees, that doesn’t mean we’re not still grappling with its complexities.

“Being at camp reminds me of the journey of long-set trauma and rebuilding for adoptive mothers and adoptive families.” —Becky

“My grandparents had a basement full of old records and CDs. I would go downstairs all alone and listen. I remember hearing a Jimi Hendrix solo and emotionally connecting with his sound. I thought, Oh my god, I am not alone.” —Mayda

Can you explain a bit more about the “model minority” myth and how it’s affected you, your family, and this work?

The model minority myth details the perceived success of Asians. It basically creates all the Asian stereotypes that deem us nonthreatening to white folks: rich, smart, obedient, et cetera.

It creates a chasm between Asians and other people of color, placing us on a pedestal while telling Black and brown folks that they are only to blame for their continued experiences with racism, poverty, and oppression.

The Asian community also falls victim to the myth by way of assimilation and an erasure of our cultural identity. It silences us, telling us we cannot complain about the microaggressions, violence, or discrimination we face, because of the privilege that comes with our proximity to whiteness. It’s a really specific type of racial gaslighting that I think is heightened for transracial adoptees.

In many ways, I assimilated into whiteness. And while I could recognize I wasn’t actually white, I did not identify as a person of color, nor did I want any part of anything related to my birth culture. It didn’t help that I was raised in white-only environments and my parents did not have the cultural cachet to introduce me to anything [else].

A lot of the adoptees I’ve talked to all grapple with our privilege and the long process it takes to finally identify as a person of color. Though we wear that badge with pride now, that transition of unpacking years of trauma, pain, and repressed emotion is never-ending.

“In my room, still slouching over my chair, I run my hands through

my dark hair. I appreciate its coarse texture, which has helped it

withstand my years of experimentation. I appreciate the fullness it

still retains despite being transformed and debased as a mockery of its

truest self for nearly a decade. I appreciate the power it holds in how I

present myself to the world, a power that has always been there, but

was long overlooked and grossly misused.” —Diana

“In my room, still slouching over my chair, I run my hands through

my dark hair. I appreciate its coarse texture, which has helped it

withstand my years of experimentation. I appreciate the fullness it

still retains despite being transformed and debased as a mockery of its

truest self for nearly a decade. I appreciate the power it holds in how I

present myself to the world, a power that has always been there, but

was long overlooked and grossly misused.” —Diana “Rooftops have always been a special place for me. There’s

something about being a KAD [Korean adoptee] in largely white community,

where it always kind of feels like I have access to freedom and power, I

have ways I can see it and play in it, but it still feels distant. And

similarly, KAD life has always felt like this weird place of being just

on the outside of things, soaking in the glorious sunshine some of the

time and being brutally exposed at other times.” —Jae Hyun

“Rooftops have always been a special place for me. There’s

something about being a KAD [Korean adoptee] in largely white community,

where it always kind of feels like I have access to freedom and power, I

have ways I can see it and play in it, but it still feels distant. And

similarly, KAD life has always felt like this weird place of being just

on the outside of things, soaking in the glorious sunshine some of the

time and being brutally exposed at other times.” —Jae Hyun

Within that, were there any notable differences between younger and older adoptees?

I was hoping to find someone 55-plus who might be considered a first-wave adoptee, but I was only able to get in contact with three adoptees in that age range — and all three of them didn’t have much to say about their adoption or identity. Obviously, that’s not a huge sample size to draw any sort of conclusion, but I presume part of it is because our generation now has the language to talk more openly about the complexities surrounding identity.

I didn’t see a notable difference between the younger adoptees and the older adoptees in the book regarding how they talk about their journey, though there was one instance in which I was talking about the many ways adoptees assimilate into whiteness, and asked the participant if they had performed whiteness. They rejected the idea of performativity because that term is too contemporary in talking about their adolescence.

Overall, I think it helped that the “older” adoptees shared similar values with the younger participants and me. They too welcomed honest and vulnerable conversation. I was so honored to have 10 incredible, brave, and beautiful humans trust me with their stories!

What are things you hope a wider audience takes away from this work?

So much of the adoptee narrative is one of sunshine, rainbows, and success. That is not the case for all adoptees. A lot of our families took the color-blind approach to race, which is not a productive perspective, because we still move throughout the world as nonwhite bodies, no matter how American or white we were raised.

Adoptees are oftentimes left out of the conversation because there is an assumption that everything is fine because we got something “good” out of this. While some adoptees may align with that thinking, I do not. Because we internalize all of that, we are silenced and alone. I want adoptees, whether they are Korean or not, to know their stories matter. I want there to be a celebration in claiming their adoptee identity.

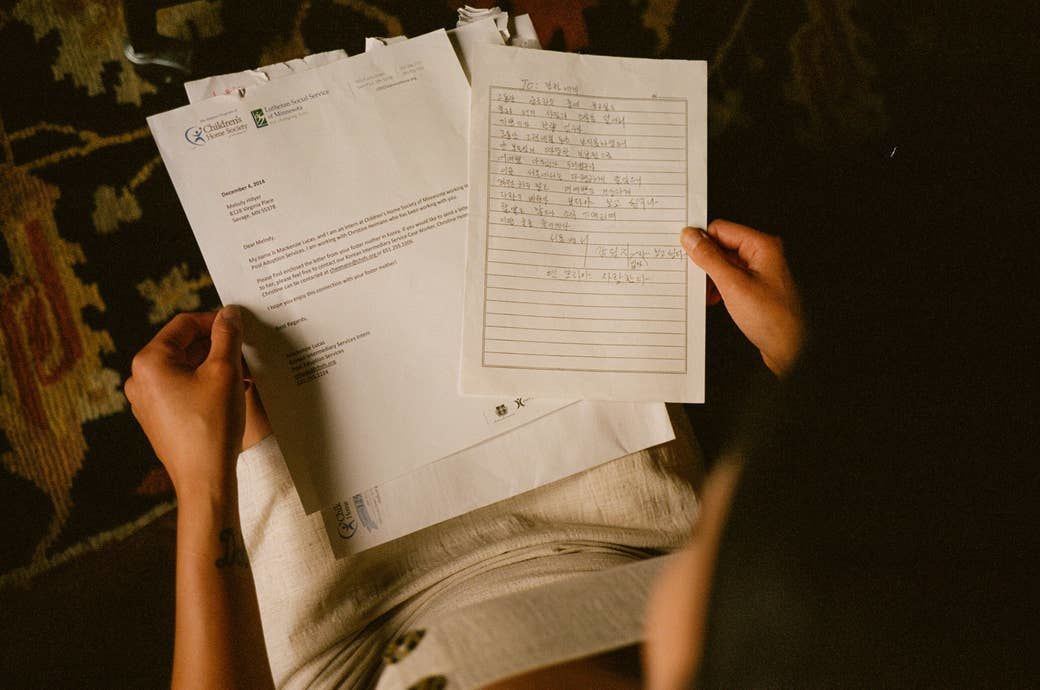

“Being a woman, a woman of color, an adoptee, my friends or

partners have to see those things in me, and you have that kind of

relationship, you don’t realize how important it is.” —Melody

“Being a woman, a woman of color, an adoptee, my friends or

partners have to see those things in me, and you have that kind of

relationship, you don’t realize how important it is.” —Melody

“I’ve been seen in all of those: in my queer identity, Korean identity,

and in my adoptee identity. I haven’t gotten that from any other place

I’ve been.” —Jeffrey

“I’ve been seen in all of those: in my queer identity, Korean identity,

and in my adoptee identity. I haven’t gotten that from any other place

I’ve been.” —Jeffrey