15 Powerful Stories Of Segregation In America

Michael Paul Williams — attended Catholic schools before enrolling in Hermitage High School during desegregation.

"I remember being in the schoolyard and hearing some of the older

kids saying this poem: 'In 1964, my father went to war. He pulled the

trigger and killed the nigger and that was the end of the war.'"

"I remember being in the schoolyard and hearing some of the older

kids saying this poem: 'In 1964, my father went to war. He pulled the

trigger and killed the nigger and that was the end of the war.'"

Laura Browder is a professor of American studies at the University of Richmond in Virginia. She recently teamed up with photographer Brian Palmer to capture 30 powerful testimonies from all walks of life in Richmond during the mid-20th century — a turbulent cultural era that saw the first integration of previously racially segregated schools in the region. The results culminate in an emotional exhibition titled Growing Up in Civil Rights Richmond and offers an invaluable record of American history from those who actually lived it.

Here, Browder speaks with BuzzFeed News on her experience researching this project and shares with us a selection of Brian Palmer's inspiring portraits from the series.

What has been your focus for this exhibition and where did research begin for you?

Growing Up in Civil Rights Richmond focuses on the experiences of Richmonders, black and white, who were actively involved in the civil rights movement as children or teenagers — as protesters, attending schools in the process of desegregation, or as the children of prominent activists whose parents’ work affected their lives.

I have been working on oral history–based, civil rights–focused projects in Richmond since 1999, when I wrote my first oral history–based drama about a historic black neighborhood that was being squeezed out by the university where I then taught, Virginia Commonwealth University — but have been able to accelerate the pace of this work since moving to the University of Richmond in 2010.

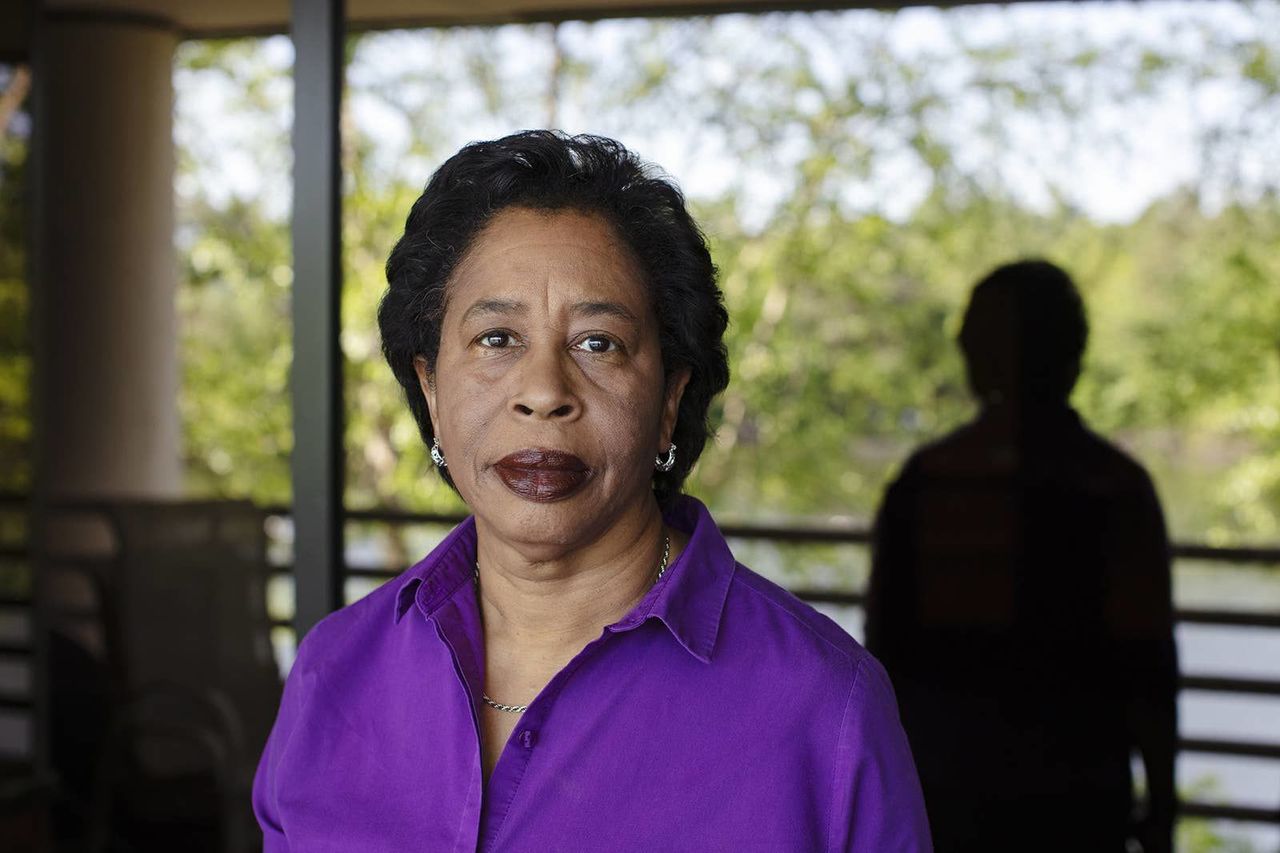

Myra Goodman Smith — attended Robert E. Lee School during desegregation.

"When I was in second grade, Martin Luther King was killed. I just

remember my mom coming home and lying on the bed and crying, and hearing

sirens all over the place. My mom told me that the next day there was a

different atmosphere when she went to work on Broad Street. People were

fearful."

"When I was in second grade, Martin Luther King was killed. I just

remember my mom coming home and lying on the bed and crying, and hearing

sirens all over the place. My mom told me that the next day there was a

different atmosphere when she went to work on Broad Street. People were

fearful."

What is it about Richmond that makes this city uniquely suited to tell these stories?

Richmond is a city that has historically been more celebrated for its Confederate monuments than for its traditions of resistance — and yet, in the 1930s, Richmond was the birthplace of the Southern Negro Youth Council, a radical civil rights group that had the support of both W.E.B. DuBois and Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Unlike Atlanta, a city where, as one of my archivist friends from there jokes, everyone who was even tangentially involved with the civil rights movement has been interviewed three or four times, Richmond has not delved deeply into its civil rights past.

And yet there was a great deal going on in Richmond — civil rights leaders, including Martin Luther King and James Farmer, came to speak here and to train Richmonders in nonviolence. One of the women I interviewed, Zenoria Abdus-Salaam, told me that Rosa Parks, who was a seamstress, helped her with her sewing homework in her home economics class.

Later in Richmond, there were chapters of the Black Panthers and of MOVE, the Philadelphia-based group whose compound was destroyed by city-ordered firebombing in 1985. But this history is rarely discussed.

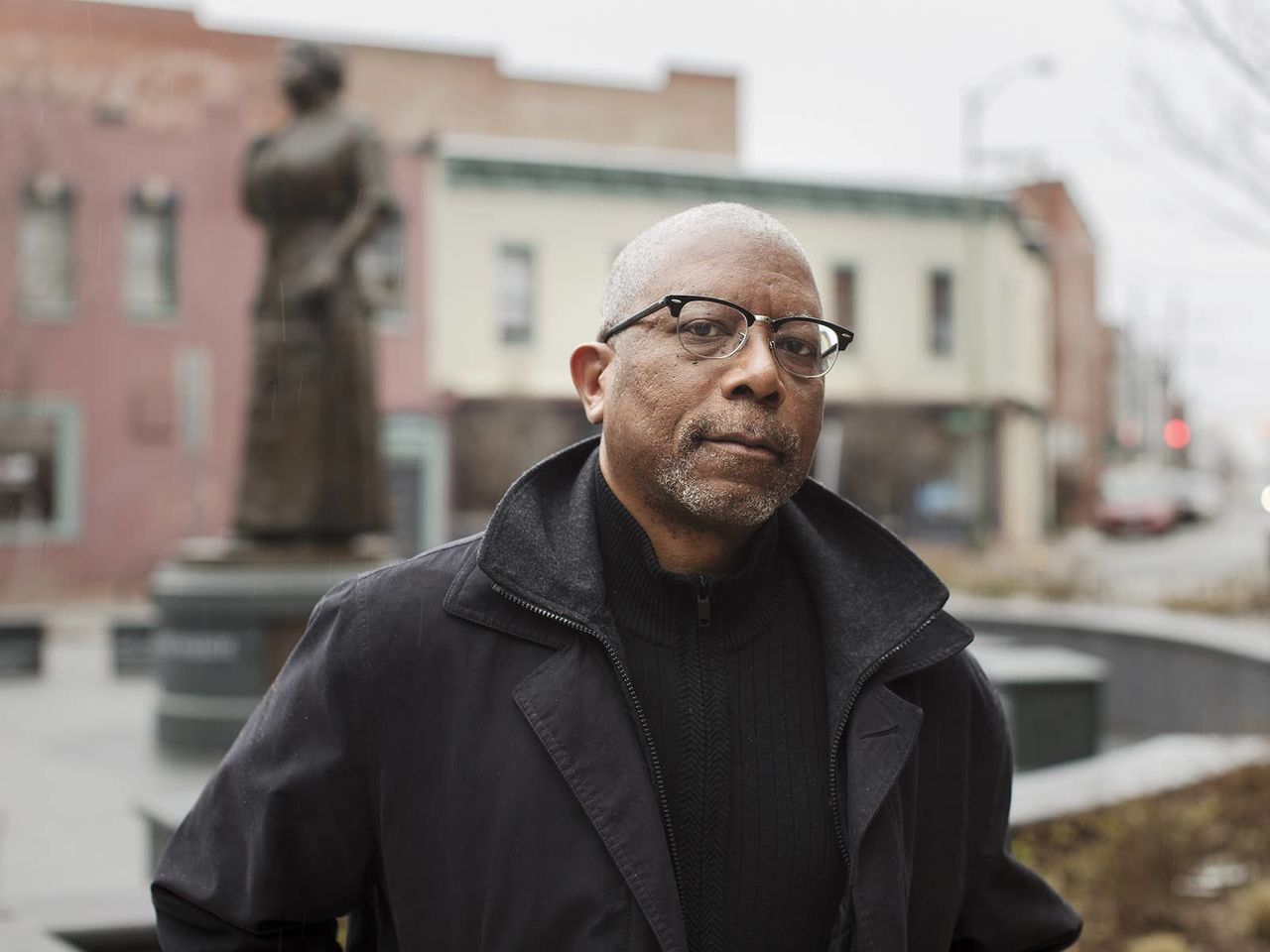

John Dorman — joined Richmond protests as a teenager during the civil rights era and attended Armstrong High School before joining the army to serve in Vietnam.

"During my year in Vietnam, there was a lot of racial tension, too.

Although we were fighting the Viet Cong, we were fighting two wars as

blacks."

"During my year in Vietnam, there was a lot of racial tension, too.

Although we were fighting the Viet Cong, we were fighting two wars as

blacks."

How did you meet your subjects?

Any way I could! I met some of my interview subjects through classes I taught with my collaborator Patricia Herrera — all of them focused on issues of civil rights in Richmond. Patricia is a theater person, so most of our classes culminate in a documentary theater production researched, written, and performed by our students.

One semester we were focused on the story of a high school, George Wythe, that had been all-white until it was integrated through court-ordered busing in 1970 — and then resegregated, becoming all-black. We had gotten involved with a group of alumni from Wythe, and one day we decided to spend a class period recording a group conversation with alums from that time. One of the alums, Mark Person, reached out to a journalist at the Richmond Times-Dispatch.

When I opened up the paper that morning and saw our classroom address and my email listed there, I had to lie down on my office floor — I had no idea what would happen or how many people would come to the class. Over 20 Wythe alums, roughly half black and half white, showed up in our class to share stories, sing together, laugh, and cry. It quickly became apparent that they had all had very different experiences.

Yolanda Burrell Taylor — one of six black children to desegregate what was then Albert H. Hill Junior High School.

"I was the first black varsity cheerleader at Huguenot. [...] And

probably much to the disappointment of a lot of my schoolmates, I became

homecoming queen."

"I was the first black varsity cheerleader at Huguenot. [...] And

probably much to the disappointment of a lot of my schoolmates, I became

homecoming queen."

Royal Robinson, an African-American man from a very poor family, thinks of busing as the best thing that ever happened to him. Other black alums mourned the fact that they were unable to participate in the rich traditions of the segregated black high schools their parents had attended. Some black and white alums talked about their fear of racial violence in high school. Yet all of them had life-changing experiences.

I reached out to many of these alums, as well as alums I met through my years of work with students and alums from Armstrong High School, arguably the oldest black high school in Richmond. I met many other project participants through word of mouth. Every time I interviewed someone, I asked that person if there was anyone else whom I should be sure to interview.

What has been your guiding motivation in collecting these narratives?

I'm currently writing a biography of my grandfather, American Communist Party leader Earl Browder, who was very active in the civil rights movement of the 1930s — he was in the forefront of the international battle to free the Scottsboro Boys, nine black teenagers given death sentences after being falsely accused of rape.

Robin Mines — was bused to a formerly white school, Elkhardt Middle School, in 1970.

"After only two weeks in our new home, our house was completely

shot up — shotgun blasts all over the front yard, windows shot out, the

aluminum siding, a whole section of the house was just bullet holes

everywhere."

"After only two weeks in our new home, our house was completely

shot up — shotgun blasts all over the front yard, windows shot out, the

aluminum siding, a whole section of the house was just bullet holes

everywhere."

When the “Growing Up” exhibition opened in January, my father, who grew up in this family committed to racial justice, was in the process of dying. As I flew back and forth from my childhood home in Providence during his last months, it was intensely meaningful for me to reconnect with all of the interviewees for the exhibition and to feel as though the struggle that my grandfather was so deeply involved with, and that my dad believed in so strongly, was continuing through these remarkable people.

What was one of the most surprising or unexpected takeaways from your research?

In our current political climate, many people have a hunger for stories of perseverance and idealism enacted during a period of political repression. These stories offered me, and I think many others, hope and a sense of community.

I was amazed at how much these long-ago experiences had shaped the lives of the participants — sometimes well into their seventies or even nineties. I would say that, almost without exception, they have continued a lifelong commitment to social justice.

What do you hope people will take away from Growing Up in Civil Rights Richmond?

I hope they understand their city in a new way and gain an appreciation for the power of everyday people to change the political system. Most of all, I hope that they will understand how many people they might encounter in their daily lives who have had these kinds of life-altering experiences — and take the time to engage with them in meaningful conversation.

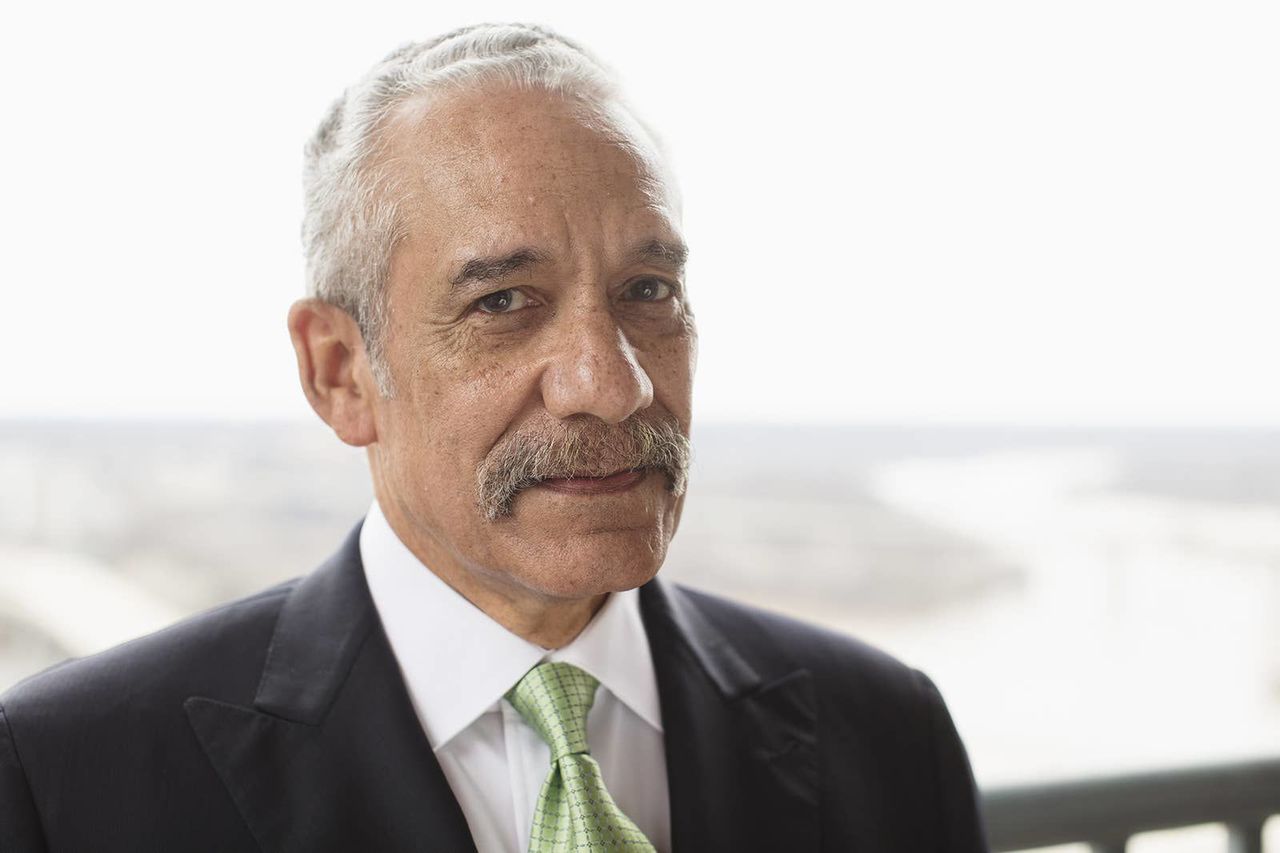

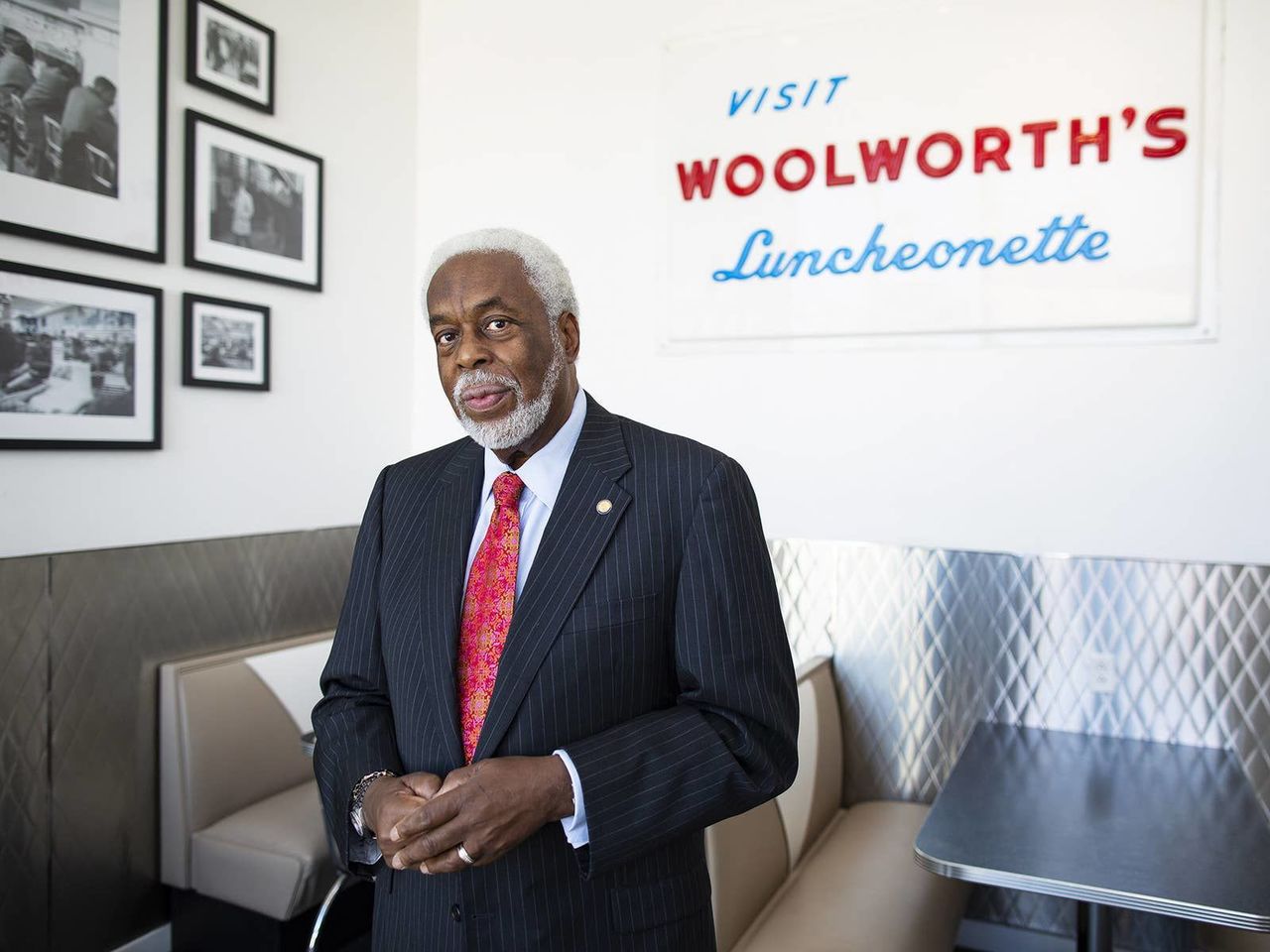

Robert Grey Jr. — during desegregation, he attended Chandler Junior High School.

"I was too young to do the actual sit-ins, but I was commissioned to be part of the community outreach that helped people be better aware of their rights, to go out and vote, and to organize around the idea that we needed better education, better jobs, and better housing."

Reggie Gordon — was among the first black students to enter his primary school in Blackstone, Virginia. He attended Richmond’s Thomas Jefferson High School as it desegregated.

"At Thomas Jefferson High School, I thought it was natural to have a very integrated circle of friends. [...] I don’t remember any tension, but then there were fewer and fewer white kids. Even some of my friends started disappearing."

Valerie Perkins — attended George Wythe High School during desegregation.

"The integrated cheering squad was a driving force for me once I joined. It was my way of attaching to a group of people, a group of allies because all of my other friends were not there. I had support and friendship, and I wasn’t just out there by myself. Maybe that’s why it got better."

Dr. Leonard Edloe — attended Armstrong High School during the desegregation years.

"My father would carry me with him to City Hall to pay the poll tax, so I was very aware of things that were going on in the city. It was just around the time when people were arrested at Thalhimers, at the sit-in, that we really became involved."

Loretta Tillman — attended George W. Carver Elementary School during desegregation.

"Once, my mother stopped at Woolworth’s; it was a whites-only lunch counter. And my mother sat herself in a booth and sat me next to her and dared anybody to say one thing. [...] My mother didn’t care; she was not having it."

Nell Draper-Winston — picketed whites-only stores in Richmond with her parents during the civil rights era.

"Once, we had a meeting at one of the churches, and someone announced that there were agitators outside and that a bomb had been placed in the building. I was very, very proud that no one left."

Philip H. Brunson III — in his first year at George Wythe High School, 1969, he was one of only a handful of African American students.

"My first year at Wythe — the fall of 1969 — there were so few blacks, you could count us in the hallway. By the fall of ‘70, the school had changed over to 85% black."

Tab Mine — was bused to Binford Junior High School during desegregation.

"George Wythe High school was a culture shock for me. I would be the only black person in the classroom. I was always the kid who liked to connect with the teacher, and I couldn’t connect with the teachers there."

Daisy Weaver — attended Armstrong High School when the first white teachers were assigned there.

"There was an article in the Richmond News Leader or the Richmond Times-Dispatch about those 'crazy black students' at Duke who took over the administration building. I remember writing a letter to the editor to say that we were not crazy; we had legitimate concerns. That was my first letter to the editor."

Deborah Taylor — attended Armstrong High School when the first white teachers were assigned there.

"I can remember going downtown, and there was a Ku Klux Klan rally going down the middle of Broad Street. I remember my mom saying to me, 'Keep walking, don’t stop.' And I’m going, 'Why? Why can’t I look at the people with the hoods on?' She’s telling me, 'If you stop, you’re gonna get hurt.'"