What we know and don't know about Covid-19

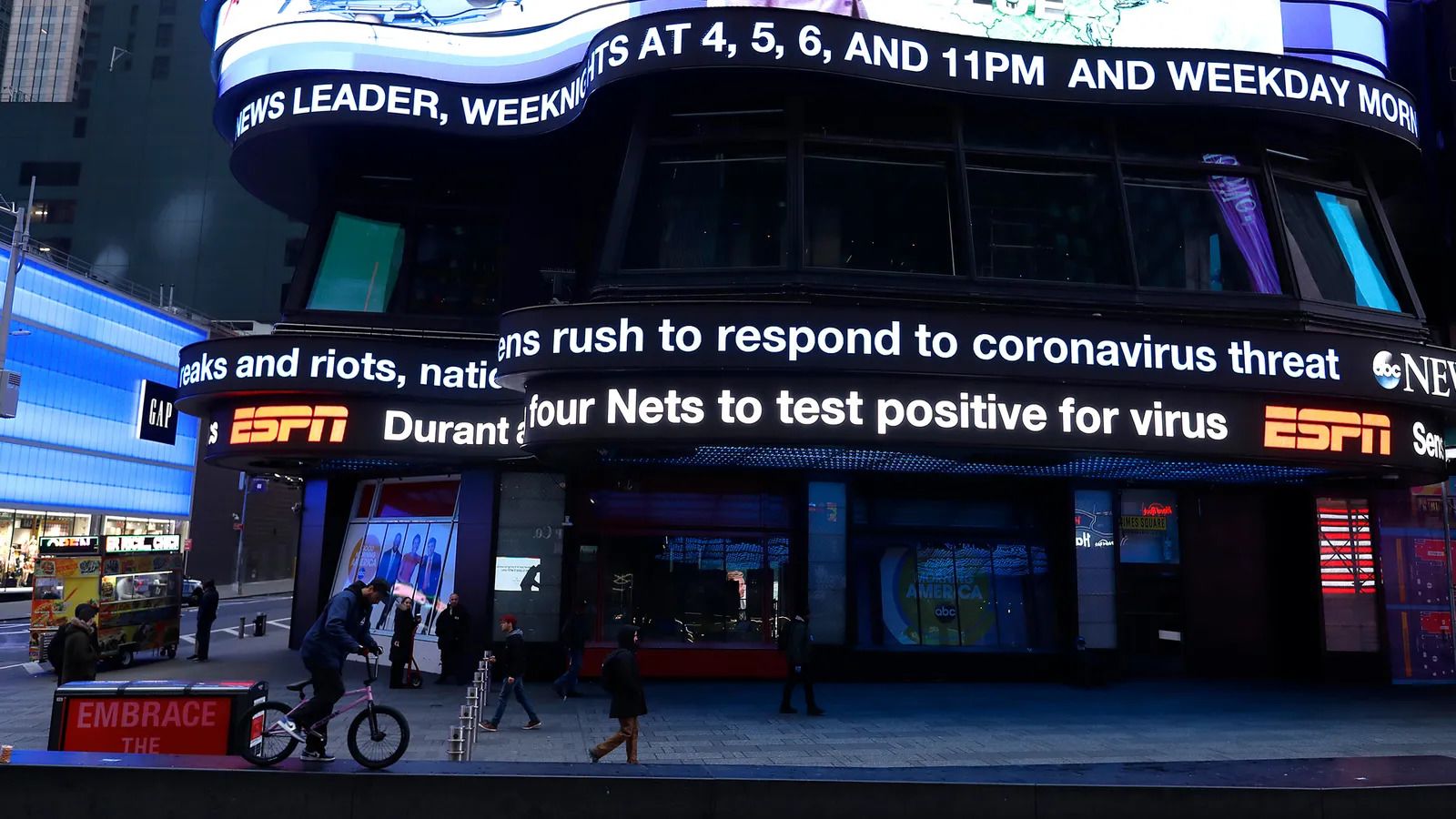

One of the challenges for understanding Covid-19 is that all the science has happened under a spotlight.

Usually, by the time you read about scientific research on a news site like the BBC, it has gone through a period of scrutiny, development and evaluation. Whether it's a breakthrough in cancer treatment, a new understanding about the brain, or a discovery about water on Mars, it is often based on a paper in a peer-reviewed journal that was submitted months ago. And the actual science itself was done at a laboratory bench, in an MRI machine or on a planetary surface long before that, possibly even years prior. That science is not secret as it's being done, it's just something people rarely pay attention to until it reaches a journal.

What's different about Covid-19 is that we all – the public, politicians, journalists – have experienced science at its frontiers. At the border between the known and the unknown, research is messy, confusing, and sometimes contradictory. Human fallibility and bias is possible. But this is how it works. This is how we find out how the world operates, and how we move forward to greater understanding as a species.

What’s different about Covid-19 is that we all – the public, politicians, journalists – have experienced science at its frontiers

We can trust that science has self-correcting measures embedded within it, because it is a shared endeavour. Findings are tested and re-tested, replicated or not, and study-by-study a clearer, slightly truer picture of the world emerges. It just takes a while to get there.

The urgency of the pandemic has not provided the luxury of time to reach consensus, smooth out differences and reject wrong turns – and this has brought with it a number of challenges. Tentative non-peer-reviewed findings have been given more weight than they would usually deserve, due to an absence of more robust evidence. In some cases, controversial single voices have been amplified. Scientists with legitimately differing views have duked it out over the airwaves for us all to hear. Meanwhile, some of what we thought we knew a year ago has changed, some of it has evolved, some is still unclear.

Over the past year, BBC Future has attempted to navigate through that fog, by providing context and delving deeper into the science of the day and the questions of the moment. Now, as we approach one year since the pandemic began, it is time to take stock. What have we learnt, and what remains unclear or unknown? And what new questions are emerging?

This is by no means an exhuastive list, and it is one we will be continually updating as we find out more. But here's a snapshot of where we stand in early 2021:

WHAT WE KNOW

Ventilation indoors matters

As the evidence has evolved, the importance of avoiding airborne contact with the virus indoors has grown. Cleaning surfaces, wearing masks and washing hands all still matter, but so does ventilating indoor environments with fresh air.

Masks work

In the absence of firm data, at first some governments, such as the UK's, were reluctant to recommend masks, while others did so anyway. The precautionary approach won out. Masks have proven to be a simple, effective way of preventing spread. Face visors, however, are less effective.

Handwashing might still be important

Amid the urgency over localised lockdowns and social distancing, another crucial factor in the fight against coronavirus was in danger of being forgotten: handwashing. Although transmission via inanimate surfaces is now thought to be relatively unlikely, there is evidence that the virus can be found on the hands of infected people and so a chance they can pass it onto others. Humans also have a tendancy to unconciously touch their own faces.

It's not yet clear what the social impact of the pandemic will be in the long term

It's not yet clear what the social impact of the pandemic will be in the long term

The virus affects people differently

As well as age differences, it emerged that the virus affected men more seriously than women, and some racial groups were more vulnerable than others. Some people also have a kind of mysterious hidden immunity, which they may have acquired long before the pandemic began.

The virus can damage organs

Though Covid-19 is a respiratory virus, it doesn't limit itself to damaging the lungs. Now scientists know that it can infect the cells that line blood vessels and affect a range of other important organs, such as the heart, brain, kidneys, liver, pancreas and spleen. The effect has been found even in young, low-risk people. No one knows how long the impairments will last, or whether they will ever fully resolve.

The virus spreads exponentially

...but most people don't understand that. A spate of studies have shown that people who are susceptible to this "exponential growth bias" are less concerned about Covid-19's spread, and less likely to endorse measures like social distancing, hand washing or mask wearing.

Coronavirus vaccines are safe and effective

Vaccine scientists moved extraordinarily fast, under extraordinary pressure. With the weight of global expectation, they have delivered safe, effective vaccines that had been rigorously tested in trials. BBC Future got first-hand experience when one of our journalists volunteered to participate in the Oxford-Astrazeneca trial (and he's still doing his weekly swabs, months later).

A single dose of vaccine provides moderate protection

But it comes with some important caveats. The extent of protection depends on the vaccine – in some cases, there isn't enough data to be sure of any just yet. Until you receive a booster dose and many more people are vaccinated, it's vital to continue social distancing, wearing a mask and following other public health advice. In fact, it's helpful to imagine that it didn't happen.

Herd immunity usually happens via vaccines

Herd immunity is a kind of disease resistance that occurs within a population, as a result of the build-up of immunity in individuals. But contrary to the impression you might have got during the pandemic, there are many reasons that it is not normally achieved by intentionally allowing a virus to spread. Many scientists now believe that any attempt to do so would have led to unacceptable levels of deaths. But herd immunity can also be acquired via vaccines, which lead to significantly less collateral damage and may provide superior protection to natural infections.

Most vaccines probably won't prevent transmission

That said, the current Covid-19 vaccines weren't judged on their ability to prevent the spread of the virus – instead, they were assessed by their ability to prevent people from developing symptoms and falling ill. Research on whether the vaccines will also prevent transmission of the virus is still ongoing, but there are some early indications that both the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine and the Oxford-Astrazeneca vaccine can reduce transmission. There are some early hints that other vaccines may be able to stop it entirely.

Death rates vary from country to country

…and there are many reasons why, to do with the way deaths are counted. One outcome of this is that it can be difficult to compare death rates in different countries. Far from being unique to Covid-19, such differences in the way deaths are counted are common when an epidemic occurs.

The pandemic has demonstrated the power of simple, everyday behaviours,

such as hand washing, social distancing and wearing a mask

The pandemic has demonstrated the power of simple, everyday behaviours,

such as hand washing, social distancing and wearing a mask

WHAT WE KNOW FROM HISTORY

This year, BBC Future has also looked to past pandemics to see what we can learn:

How earlier pandemics were contained

The way countries like Canada and Taiwan dealt with the Sars outbreak of 2003 carry many lessons for the current coronavirus pandemic, including the importance of tracking down the contacts of infected individuals, and treating the sick in isolation wards.

Social distancing is over 400 years old

In 16th-Century Sardinia, a doctor published a guide to social distancing during a plague outbreak that seems tailor-made for coronavirus – right down to the recommendation that only one person per household should leave to do the shopping.

Vaccine rollouts require trust

In 1976, the US botched a vaccine rollout and lost the public trust. The event holds lessons for national vaccination efforts today.

There has been little time to check scientific findings before they're circulated to the public during the pandemic

There has been little time to check scientific findings before they're circulated to the public during the pandemic

WHAT WE DON'T KNOW

The science is ongoing, and we're still learning about this virus all the time. Here's a snapshot of a few unknowns that hopefully researchers will soon understand better:

The long-term effects of the disease

How long will people with Long Covid be affected for? What will the epigenetic impact of the virus be? (In other words, will its effects be passed through generations?) And that's not to mention the social/economic impact…

How the virus will evolve

Every time the coronavirus passes from person to person, it picks up tiny changes to its genetic code, but scientists are starting to notice patterns in how the virus is mutating.

What the next pandemic could look like

Which diseases are most likely to cause the next global pandemic? In recent weeks, BBC Future has been exploring six of the diseases most likely to cause the next one, and examining the work being done to try to stop them.

What is the pandemic's environmental impact?

Although short-term emissions of greenhouse gases and air pollutants dipped significantly at the beginning of global lockdowns, they quickly rose again over the rest of the year. Overall, CO2 emissions fell by just over 6% in 2020. But there is a chance that the pandemic will have a longer-lasting impact, as environmentalists ask whether our Covid-19 crisis-response mode could help model our response to climate change.

Please come back again in the future to find out what else we have learned and as we start to get answers to some of the unknowns.