How Hedges Became the Unofficial Emblem of Great Britain

Welcome to Hedgeland. The streets of suburban Britain are edged with merry green. Boxy bushes of privet, beech, holly, yew and other plant species act as boundaries around gardens, demarcating property lines and separating our domestic and public lives. Town planners call them “woody linear features,” but they are so much more than that.

They are a charmed circle drawn around family and self. What the white picket fence is to America, the hedge is to Britain, a cozy symbol of conservatism. The distinctive sound of a British summer, apart from the melancholy hiss of rain, is the insistent growl of the motorized hedge trimmer, the staccato rasp of hand shears. Hearken to those blades; every snip is a snipe: “Mine. Not yours. Keep out.”

On a recent morning, I took a walk through the northern suburbs of Edinburgh. The ancient castle and bristling swoosh of a skyline that make Scotland’s capital so romantic could not be seen from here, for I had entered the realm of the hedge.

They are so mundane, hedges, as to be almost invisible. Yet allow eyes and mind to refocus, and banality yields to fascination. One begins to suspect that hedges are psychological portraits of those who live behind them. A hedge left wild and overgrown suggests a certain lassitude, especially when growing right next to one pruned with geometric rectitude.

Outside the home of J.K. Rowling, a towering barrier of leylandii screens the 17th-century manor house from the road; little more than its chimneys and central tower are visible through the green parapet. Cupressocyparis leylandii is the Voldemort of hedges, a sunlight-blocker loathed by many unfortunates whose gardens fall in its shadow; it grows three feet or more per year. Those with a need for privacy, however, regard leylandii as the next best thing to an invisibility cloak.

On a handsome terrace a few miles east, an ordinary privet has been transformed into an ocean liner, complete with cresting wave. It is around eight feet tall from seabed to twin funnels, and nearly as long from bow to stern. It has grown, during the past 39 years, around three feet in every direction. This is the work of Edwyn Newman, 73, a retired electronics engineer.

He has been clipping that ship into shape since he was a youngish man and his son and daughter were small. “My great-great-great-grandfather was one of five brothers, all of whom were master mariners,” he tells me, “and my mother was a Wren [a member of the Women’s Royal Naval Service] during the war, so there’s bit of sea in the blood,” he laughs. “But mainly I just thought it would be fun.”

The Great British Hedge is thought to have its origins in the Bronze Age, and perhaps even in the earlier Neolithic period. Hedges were then used to manage cattle, keeping them separate from crops. An archaeological excavation in Cambridgeshire has revealed a sprig of blackthorn, believed to be a hedge remnant, dating from around 2000 B.C.

Management of hedges for agriculture continued under various invading cultures: first the Romans, then the Saxons. The Old English word haga, meaning hedge, is found in legal documents pertaining to land ownership. Hedges of sufficient thickness and thorniness may even have been used as military defenses.

Privet is mentioned by Pliny the Elder in his Natural History. Pliny writes that Gaius Matius, a friend of Julius and Augustus Caesar, invented the art of clipping hedges for ornamental rather than strictly pragmatic purposes; Matius also translated The Iliad into Latin, thus doing a favor to both Homer and homeowners.

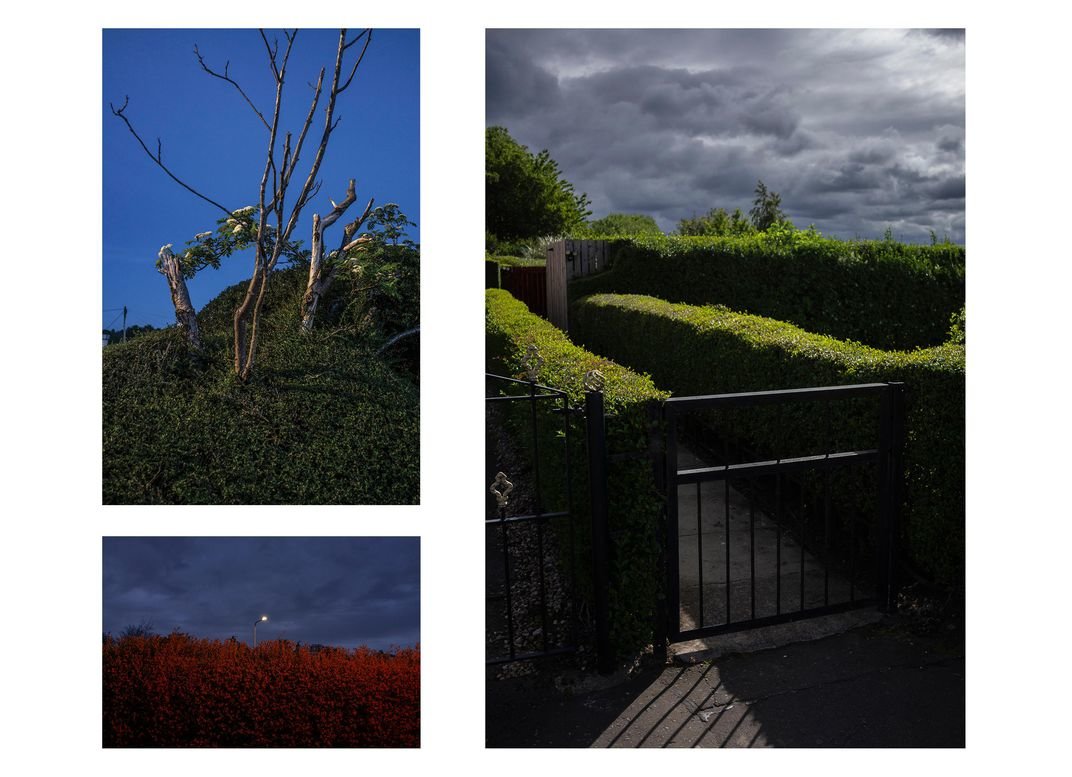

Ecologists have recorded a diverse group of wildlife in hedges,

including 60 species of nesting birds. Hedges form a boundary at the

entrance to a garden in Ravelston, Edinburgh.

Ecologists have recorded a diverse group of wildlife in hedges,

including 60 species of nesting birds. Hedges form a boundary at the

entrance to a garden in Ravelston, Edinburgh.

Hedges tend toward anonymity. Unlike trees—those divas forever celebrated for their lofty nobility and sentinel grace—hedges produce few stars. Which is not to say there are none. The so-called Phoenix Hedge, in the Bristol suburb of Henleaze, is 295 feet long and made up of several species including ash, elm and dog rose.

Around 800 years old, it is a survivor. Age in hedges is, however, a slippery concept. They yearn to stretch up and become mature trees, but pruning keeps them forever young. “A hedge is in a state of suspended animation,” says Chris Crowder, head gardener at Levens Hall, a grand manor in Cumbria in the north of England. “The individual plants may be ancient and gnarled, but because they have never been allowed to grow into a tree, they never reach old age.”

No one, surely, understands hedges more intimately than Crowder. The grounds of Levens Hall are ornamented by the world’s oldest topiary, first clipped into phantasmagorical shapes—peacocks and chess pieces, lollipops and lions—in 1694. Crowder is responsible for maintaining about 100 pieces of topiary as well as a double beech hedge ten or so feet tall, much the same width, and around half a kilometer long.

He is only the tenth head gardener in all these centuries, and lives in the house built for the first, looking out at the foliage that is his inheritance and Sisyphean task. He has had the job for 34 years. It is not clear who is the master, he or the hedges, but Crowder has come to appreciate the long months of pruning as an almost Zen experience. “What people don’t appreciate enough is the simple pleasure of taking time and care to handcraft something,” he says. “The concentration is very therapeutic.”

The British urban hedge as we know it first flourished between the wars. Suburban semidetached houses needed something between and around gardens to mark property. Enter the hedge. Enter, too, almost immediately, the association between hedges and conformity.

In George Orwell’s novel Coming Up for Air, George “Fatty” Bowling looks out one sour morning over a poky back lawn enclosed by privet and feels trapped. In the Harry Potter books, the beastly Dursleys live on Privet Drive, their address shorthand for the small-mindedness of suburbia.

In Elizabethan England, a person could be placed in stocks for at least two hours for breaking a hedge. A selection of hedge topiary in Craigleith, Edinburgh.

In London, during this strangest of years, hedges came to reflect the national mood. In Herne Hill, where the Victorian polymath John Ruskin had, as a child, admired a garden hedge of gooseberry and currant bushes, the letters “BLM,” for Black Lives Matter, were sheared into a privet.

In Walthamstow, birthplace of the 19th-century textile designer William Morris, who once created a topiary dragon from a yew in his garden, another privet became a public statement: Hannah Auerbach George, a weaver in her 20s, took up her trimmer and cut “NHS,” for the National Health Service, Britain’s system of free universal health care, into the hedge in front of her house—an expression of solidarity with those on the front line of the battle with the coronavirus.

Yet hedges do not always bring people together. This past summer, at my home in Glasgow, I noticed that my neighbor’s gardener was cutting the hedge that separates our properties. I had trimmed this only the week before, employing my signature rough-and-ready style. Now the gardener was making it so flat that one could play billiards on top.

I sallied forth and questioned his technique. He questioned mine. This was a debate with deep roots. My approach—nature finessed by human artistry—goes back to Lancelot “Capability” Brown, the landscape architect of the mid-18th century. My neighbor’s gardener, favoring a greater formalism, allied himself with André Le Nôtre, the genius of Versailles. He defended this position, not in French, but in vigorous Scots: “You’re aff yer heid! Crazy! Sick!”

This was unpleasant, but such conflicts can escalate. In 2003, an argument over a hedge led a man to shoot his neighbor and then take his own life. Two years later, a man in his 70s was found guilty of urinating, under cover of night, on his neighbor’s leylandii—a long-term campaign to kill the hedge that earned him a tabloid nickname, the Midnight Piddler.

The neighborhood hedge dispute is a British newspaper staple. The hedge, in British culture, has a fragile dignity; it is always at risk of being considered a joke. Which is unfair. Hedges, explains Tijana Blanusa, of the Royal Horticultural Society, “are an undervalued form of urban green infrastructure.” Her research has found that garden hedges provide an effective filter between our homes and traffic pollution, and they mitigate flooding, reduce noise and act as wildlife corridors.

Hedges are also an admirably versatile metaphor. In Brexit Britain, they are a barrier. In Covid Britain, they are a frontier: this far but no farther. Most of all, in a Britain battered by recent economic and political storms, they are a much-needed hug. Other nations love their hedges, too, of course, but only in Britain do they seem so bound up with national identity.

The hedge speaks to the romantic idea of the country as a green and pleasant land, but its cheerful dullness undercuts this notion before we get too carried away. Our souls are in those hedges and those hedges are in our souls.