East of England Ambulance Service: 'If we are queuing, we can't get to patients'

The area covered by the East of England Ambulance Service's nearly 400 front-line ambulances is vast.

It is responsible for more than six million people over a 7,500 sq mile (19,424 sq km) area, which includes Bedfordshire, Hertfordshire, Cambridgeshire, Essex, Suffolk and Norfolk.

The BBC joined one of the service's ambulance crews for a 12-hour shift, to see the work they do and to hear their concerns about the current state of the health service at large.

'It is very reassuring'

Pat Clarke has chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and breast cancer

Pat Clarke has chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and breast cancer

The first call-out received by the Gorleston-based crew in Norfolk is for a patient in cardiac arrest.

However, after putting on the blue lights, the crew is stood down and later diverted down to Oulton Broad in Suffolk to check on 82-year-old Pat Clarke.

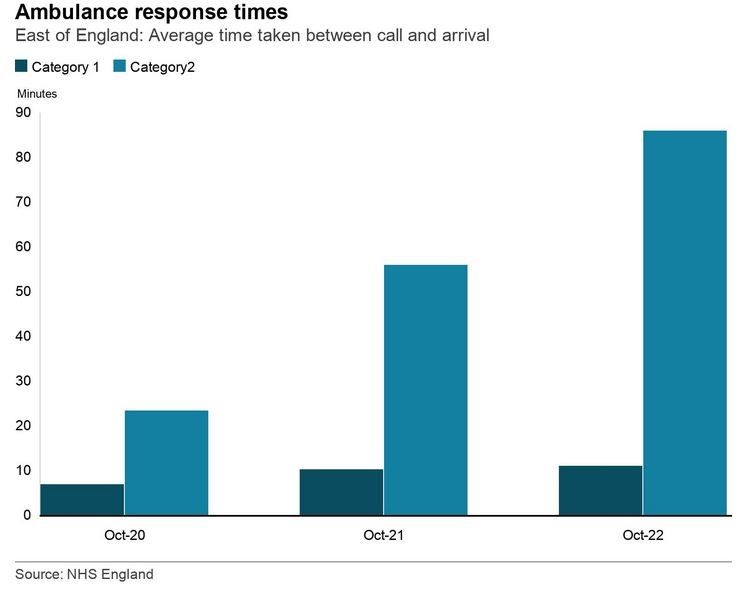

Ambulance call outs are categorised into four levels of seriousness, from Category 1, involving life threatening conditions, to Category 4, which is a non-urgent problem that requires transportation to a hospital or clinic.

This is a Category 2 call-out, which means it is a serious condition such as a stroke or chest pain.

The crew arrives within 30 minutes of the call coming in.

Ms Clarke has chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and breast cancer. Her carer, Chloe Tiborcz, was concerned about Ms Clarke so dialled 111.

Chloe Tiborcz was worried about Ms Clarke's condition so called 111

Chloe Tiborcz was worried about Ms Clarke's condition so called 111

"I came in this morning and Pat was very breathless and had a cough as well, so I called the ambulance," Ms Tiborcz says. "They came pretty quickly - within half an hour.

"It is very reassuring - I had a lady who had to wait eight hours pretty recently."

The paramedic crew says Ms Clarke could have been dealt with by a visit from her GP. But with GPs sometimes having to see up to 60 patients a day, they no longer have the resources to do such visits.

As it is, Ms Clarke does not need a hospital visit and is left to recuperate at home.

'Do one job at a time'

Ed Wisken has been a paramedic for 13 years.

An advanced paramedic specialising in urgent care, Mr Wisken says: "It is really sad to see patients who have had to wait such a long time for an ambulance - but this is just the culmination of years of underfunding and of reduced resources peaking now where demand outstrips supply."

"It is upsetting to see it," he says. "It is not nice to see people who have been waiting hours and hours for an ambulance - but we have really hit crisis point now."

He says the morale of fellow paramedics and other healthcare workers is currently very low.

"The key is you just have to do just one job at a time and just take the patients that you see and do the best for them," he says.

"If you worry about the bigger picture too much you will get frustrated and angry - but that's not going to be beneficial for yourself or your patients."

A suspected stroke

Paramedics tend to 97-year-old Eva Denny who has been mostly in bed since she was released from hospital

Paramedics tend to 97-year-old Eva Denny who has been mostly in bed since she was released from hospital

From Oulton Broad, the crew is then called to Thorpe St Andrew, near Norwich, to see 97-year-old Eva Denny.

The emergency services were called because those around her feared she may have had a stroke.

Family friend Yvonne Pechey says Ms Denny recently spent five weeks in hospital. During her stay, she went from being able to get around using her walking frame to losing the use of her legs.

Family friend Yvonne Pechey says Ms Denny recently spent five weeks in hospital

Family friend Yvonne Pechey says Ms Denny recently spent five weeks in hospital

The paramedics check Ms Denny over and find she has an infection.

Antibiotics are prescribed, but the crew has to wait more than 90 minutes for a GP to call them back to discuss medicine and a plan for Ms Denny's future care.

The GP wants to have her taken to hospital, but the family says given her previous deterioration in hospital they want her to stay put.

Instead, Ms Denny's infection will be managed at home.

'Only deal with the here and now'

Anna Savage, an emergency medical technician, says she "kind of stumbled" into the ambulance service

Anna Savage, an emergency medical technician, says she "kind of stumbled" into the ambulance service

Anna Savage is a former estate agent who "kind of stumbled" into the ambulance service.

An emergency medical technician, Ms Savage says she applied to the East of England Ambulance Service after speaking with friends already working there.

"I thought it would suit me, not being in an office job but being out and about and I haven't looked back," she says. "I enjoy it and I want to keep going."

"Every day is different," she says. "I knew it could be a strain on you and your family life and I wasn't under any illusions.

"Delays at the moment are a big challenge for us to deal with."

She says she senses the frustration felt by patients and their loved ones experiencing ambulance delays.

"And we can't really give them an answer either, we can only deal with the here and now and each situation."

She wants the service to find a way of reducing such delays.

'The seizures are so severe'

Max is taken straight to the children's assessment ward at the Norfolk and Norwich Hospital

Max is taken straight to the children's assessment ward at the Norfolk and Norwich Hospital

The third call takes the crew to a house near Wroxham, in Norfolk, where nine-year-old Max has complex epilepsy.

He experiences up to 30 fits each day.

His mother, Amy, administers midazolam as prescribed but, because it is strong medication, Max needs monitoring.

The crew takes him straight to the children's assessment ward at the Norfolk and Norwich Hospital.

Max's mother Amy says knowing the ambulance service would be there for her son gives her reassurance

Max's mother Amy says knowing the ambulance service would be there for her son gives her reassurance

Amy says dealing with Max's condition is "really difficult".

"They still don't really know why he has these seizures," she says. "It impacts on his quality of life and on our family life.

"He's under a professor in the United States and is having tests at Great Ormond Street, but it is really hard when someone cannot tell you what is wrong with your child.

"They don't know why his medicine does not control his seizures, so he can't live a normal life at the moment.

"The seizures are so severe that they always require medical intervention and he spends the majority of his life in a hospital.

"It is really tough."

On this occasion, both a land ambulance and the East of England Air Ambulance were sent to Max's aid.

"Being surrounded by people who are able to help him in that situation makes me feel a bit safer, because I just panic like any mum or dad would."

'We can't get to patients'

Leading operations manager Stuart Knight says delays outside hospitals are not good

Leading operations manager Stuart Knight says delays outside hospitals are not good

Stuart Knight is the leading operations manager at Gorleston ambulance station.

"We are experiencing handover delays at the hospital, which is obviously impacting wider in the community. It is a national pressure at the minute.

"Our crews are late off and it impacts on our vehicle availability for the next day.

"They can be anywhere from Cambridge to Ipswich, so they are driving a hell of a lot of miles and, if they are late off on top of that due to delays or if they get a late job, then that impacts on the following day because obviously they need an adequate rest period before they come in for their [next] shift.

"We've got welfare ideas to help staff and we are working with colleagues in the hospital to try and reduce delays.

"The last thing we want is for patients to be stuck in the back of an ambulance for 10 to 12 hours. It is not great for patients, it is not great for the crew. When that happens we can't get to patients in the community."

A Department of Health and Social Care spokesperson said: "Nobody should have to wait longer than necessary for emergency care, which is why we are taking urgent action to support services.

"This includes an extra £500m to speed up hospital discharge and free up beds - the details of which were announced on Wednesday - getting ambulances back on the road more quickly, delivering 50,000 more nurses, increasing the number of NHS 999 and 111 call handlers and creating the equivalent of at least 7,000 more beds."