Banks not passing on higher interest rates to savers mean customers miss out on £23bn

Households are missing out on £23bn a year because banks are not passing higher interest rates to savers, a Sky News analysis shows.

Although mortgage holders have been hit with higher borrowing costs, banks have been slower to pass on rate rises to savers.

Politicians accused retail banks of taking advantage of rising interest rates to bolster their own margins at the expense of customers.

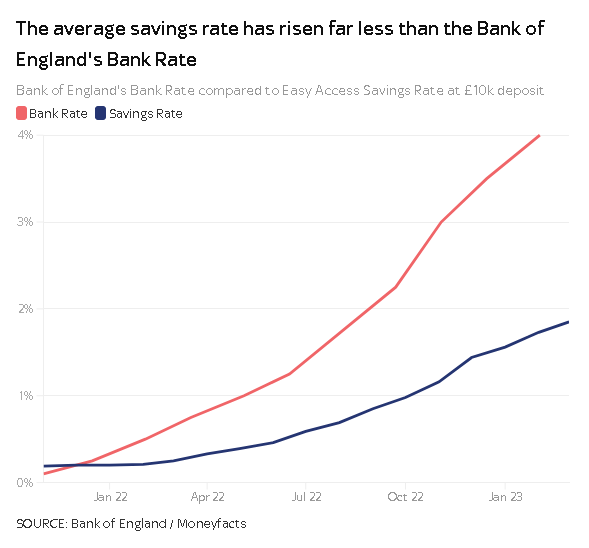

The Bank of England has raised interest rates consistently since December 2021, taking the base rate from a record low of 0.1% to 4%.

Meanwhile, the average easy-access savings rate has risen from 0.2% to just 1.88%

It means that households with savings of £30,000 stand to earn just £569 in interest per year.

If rate rises were passed on in full, this would jump to £1,253. Across the country households are missing out on £23 billion in lost interest, according to an analysis by Hargreaves Lansdown.

Banks benefitting

However, commercial banks have benefitted by widening the gap between what they pay savers and charge borrowers, also known as the net interest margin.

Britain's four largest banks all recently reported that they have widened this margin.

NatWest's margin has increased by 24%, Lloyds Banking Group's is up by 16% and Barclays by 13%.

Profits and chief executive pay have also jumped as a result.

Lloyds' profit rose 80% in the final quarter of 2022, while HSBC recorded a 90% jump. NatWest, which is still 45% state owned, recorded its best performance since the financial crisis last year.

The recent spike in bank profits comes after a decade of ultra-low interest rates that squeezed their margins.

Banks are under no obligation to pass on higher rates to savers and have been able to keep rates low because customers are reluctant to shop around for better deals.

Call for windfall taxes

However, that hasn't stopped the clamour for windfall taxes, which has grown in response to soaring bank profits.

Harriet Baldwin, MP for West Worcestershire and chair of the Treasury Select Committee, said: "We think it is pretty preposterous that at a time when the Bank of England is raising rates, they're not passing on that increase to their savers and I think the way we develop a savings habit in this country again is if savers feel that they're being treated fairly by their banks and that's what we hope to see."

Some economists have suggested that policymakers compel banks to pass on higher rates to savers.

Commercial banks hold billions of pounds in bank accounts with the Bank of England and these "reserves" are paid the bank rate of interest, 4%.

Frederic Malherbe, professor of economics and finance at University College London, said interest payments on reserves held with the central bank should be made conditional on banks passing the higher rates to their saving customers.

It could also help the Bank of England with its ambition of taming inflation.

The bank has been raising rates to dampen demand in the economy.

This is achieved by raising the cost of borrowing and the rate of saving - thereby discouraging consumption and investment.

While banks are passing on higher rates to borrowers, the other side of the equation has not been working as effectively.

"They [policymakers] want borrowing rates, mortgage rates and the rate at which businesses borrow money to go up. That's working very well. The part on savers is not working as well," said Professor Malherbe.

"That decreases the efficacy of monetary policy."

He added: "By compelling banks to pay better rates to savers, that will improve the transmission of monetary policy and the central bank will have to raise rates less."