Britain’s rule of Hong Kong was ‘occupation’, say draft teaching materials for revamped liberal studies

Britain’s rule of Hong Kong was an “occupation which violated international conventions” according to draft teaching materials for revamped liberal studies courses that a major publisher has sent to teachers throughout the city.

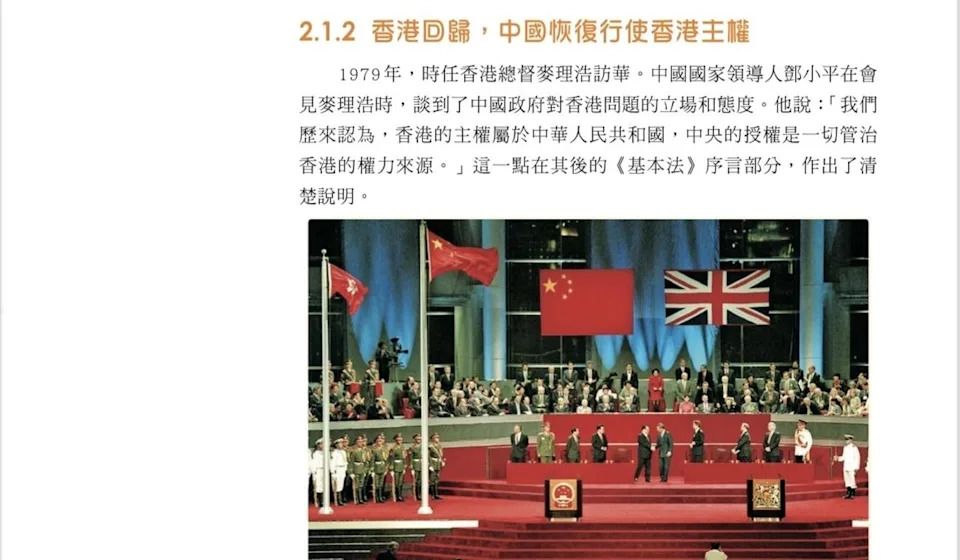

The learning materials also described the return of government to China in 1997 as Beijing “resuming the exercise of sovereignty over Hong Kong”, whereas “handover” was exclusively used to describe the event in the company’s textbooks for the subject before.

Teachers said the revisions, which were part of a wider revamp of the mandatory subject for older students, could narrow room for classroom discussion of Hong Kong history.

Do you have questions about the biggest topics and trends from around the world? Get the answers with SCMP Knowledge, our new platform of curated content with explainers, FAQs, analyses and infographics brought to you by our award-winning team.

New liberal studies teaching materials developed by Ling Kee Publishing.

New liberal studies teaching materials developed by Ling Kee Publishing.

“If this is the only narrative that Hong Kong teachers can teach students, we may only be able to touch on this one sole perspective in future,” said one educator with more than a decade of experience.

The materials developed by Ling Kee Publishing were sent to schools this week to help teachers prepare classes for Form Four students starting in September when the overhauled subject will be renamed “citizenship and social development” with a greater emphasis on patriotism, national development and lawfulness.

Publishers have been distributing new teaching materials to schools recently but all of them must be vetted by the Education Bureau under changes adopted last year.

Ling Kee’s version also said the Chinese government had “never recognised the effectiveness of unfair treaties” between the Qing dynasty (1644-1911) and Britain.

“Over the more than 100 years before the handover, Britain’s governance of Hong Kong was an act of occupation which had violated international conventions,” the book stated. “China did not recognise unequal treaties and had never given up sovereignty over Hong Kong’s territories.”

Britain took possession of Hong Kong in three waves. The queen of England and the emperor of China ratified the Treaty of Nanking in 1842, ceding Hong Kong Island to Britain, with control of Kowloon Peninsula following under the Convention of Peking in 1860. The New Territories were added under a 99-year lease in 1898.

Another veteran liberal studies teacher said he had not seen the phrase that Britain’s “occupation of [Hong Kong] had violated international conventions” in school textbooks before and which was in contrast with many Hongkongers’ understanding.

The new materials developed by Ling Kee Publishing were sent to schools

this week to help teachers prepare classes for Form Four students.

The new materials developed by Ling Kee Publishing were sent to schools

this week to help teachers prepare classes for Form Four students.

“Questions will arise among many people why the narrative of Britain occupying Hong Kong illegally should prevail,” he said. “Students may also question if the subject acts as a purpose of political propaganda and if teachers are helping to promote that.”

The latest changes are in line with broader trends in Hong Kong. Previous editions of some publishers’ history textbooks, including one from Ling Kee, had used the description of China “resuming the exercise of sovereignty” over Hong Kong.

In 2018, the government’s protocol office edited language on its website to remove mention of “handover of sovereignty”, while education officials had requested at least one history textbook replace the words “taking back” to describe the 1997 event as education minister Kevin Yeung Yun-hung said China had “always had sovereignty over Hong Kong”.

Beijing also used the term “resume the exercise of sovereignty” over Hong Kong in the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration, while Britain said “restoring Hong Kong” to China.

The preliminary revisions also reflect the government’s increasing emphasis on national security.

Apart from detailing the four offences listed under the Beijing-imposed law, namely secession, subversion, terrorism and collusion with foreign forces, the materials stress an individual’s responsibility to protect national security, saying the law could “stabilise society, improve investments and protect human rights”.

New liberal studies teaching materials developed by Ling Kee Publishing.

New liberal studies teaching materials developed by Ling Kee Publishing.

Unlike previous liberal studies textbooks that gave opposing political views, the new materials omitted mention of the wide public backlash to the law, a change teachers said was “not unexpected” given that previous guidelines from education authorities stressed the topic was not up for debate.

Liberal studies, which was introduced in 2009 to raise students’ social awareness and develop their critical thinking skills, came under attack by pro-Beijing politicians who blamed it for radicalising young people during the 2019 anti-government protests.

An Education Bureau spokeswoman said Ling Kee’s books had not been reviewed and discussions with publishers on vetting arrangements were ongoing.

She added that “Hong Kong is an inseparable part of China” and teaching materials should help pupils “correctly” understand the relation of Hong Kong to the nation.

The Post has reached out to the publisher for comment.