A Warrior’s Soul: The Alcoholic Who Became a Deadly UFC Champion

Born in a favela in São Paulo, Alex Pereira dropped out of school to work in a tire shop and soon fell into alcoholism. But he took all the hardship life threw at him, focused it inside the octagon — and against all odds, became a world champion.

From the Streets to the Octagon

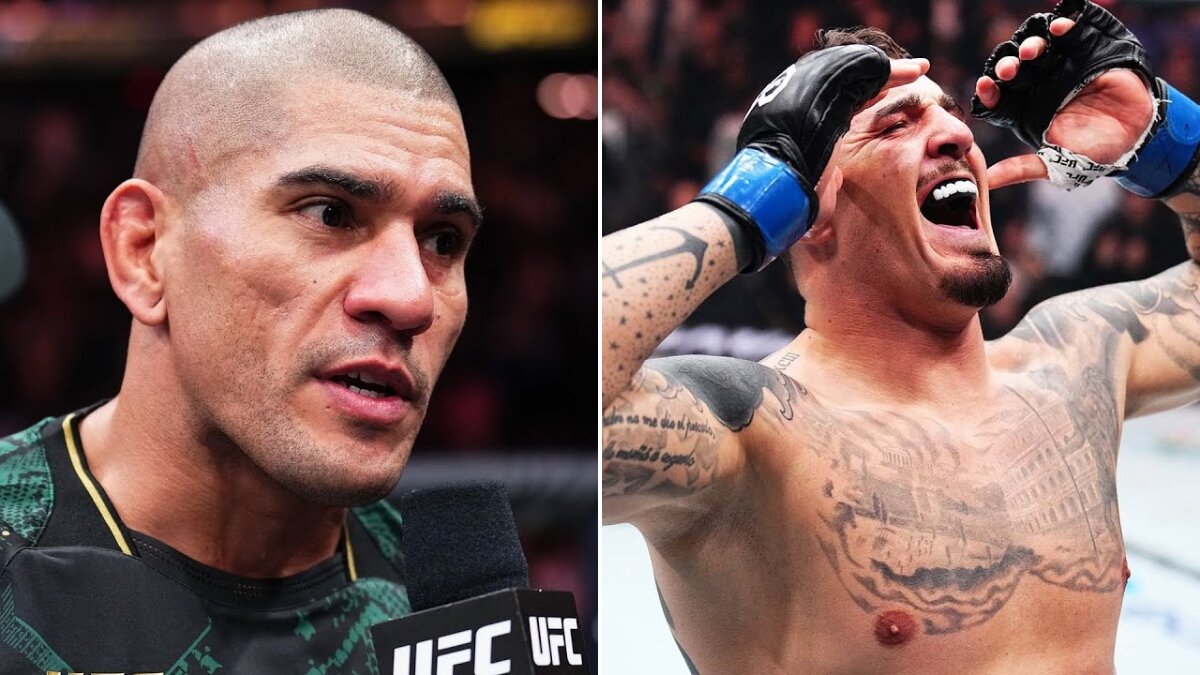

What was meant to be one of the closest and most dramatic fights in Ultimate Fighting Championship history quickly turned into a statement. After months of anticipation, light heavyweight champion Magomed Ankalaev stepped into the octagon against former champion Alex Pereira. The Brazilian dismantled his Russian opponent in just a minute and a half, reclaiming his title.

Ankalaev had taunted Pereira in the lead-up to the fight. Pereira’s signature catchphrase, “Chama” — meaning “flame” in Portuguese but used colloquially as “let’s go” — became a target. “No more Chama,” Ankalaev said after defeating Pereira the previous March.

But after knocking him down and unleashing his joy following months of restraint, Pereira shouted his favorite word back at his opponent, pointing mockingly as social media erupted and turned him into a viral meme. Analysts called it “the moment the UFC needed.”

A Childhood with No Way Out

Pereira came from nothing. He grew up in a São Paulo favela and left school to help support his family. He worked as a construction worker and later at a tire shop, where the environment led him into heavy drinking — eventually consuming several liters of alcohol a day.

In an article he once wrote, Pereira explained that soccer was considered the only escape from poverty and addiction — but he hated the sport, and “people thought something was wrong with him.” What began as a habit of drinking after work spiraled into full-blown addiction, leaving him hopeless.

Everything changed when he discovered martial arts. Training forced him to give up the destructive habit he had carried since the age of thirteen. At twenty-one, Pereira realized he could channel his anger into fighting — and that he had a natural talent for a sport he’d never even considered as a child.

From Addiction to Discipline

He began his career in kickboxing and quickly rose to champion status, but alcohol continued to hold him back. Then, in a story worthy of a film, Pereira met a coach with Indigenous roots who introduced him to the traditions of the Pataxó tribe — a small community of several tens of thousands in Brazil.

The coach provided herbal substitutes for alcohol, performed tribal rituals with him, and eventually helped him overcome his addiction — even though Pereira sometimes secretly spiked his coffee with alcohol so the coach wouldn’t notice. Today, he lives an almost monastic lifestyle.

“It’s hard for me to watch others drink,” he admitted. “But I know I can’t have just a little. It won’t stop at one beer — I have no self-control.”

Pereira embraced this tribal identity, even though he grew up in an entirely urban environment. Over time, speculation arose that he had Indigenous roots, and he began appearing in traditional clothing. Whether he truly belonged to the tribe no longer mattered — they considered him one of their own. The tribal chief even made him ceremonial outfits adorned with feathers, and Pereira adopted the nickname “Poatan” — meaning “Stone Hand.”

Rise of a Knockout King

With his body and mind rebuilt, Pereira unleashed his athletic potential. In the kickboxing ring, he gained a reputation as a brutal knockout artist, capable of ending fights with a single blow. His left hand — the “stone hand” that inspired his nickname — became a weapon of destruction.

One of its early victims was Israel Adesanya, a charismatic and outspoken New Zealander regarded as a rising star. Between 2016 and 2017, the two fought twice in the kickboxing ring — encounters that laid the groundwork for a fierce rivalry. Calm and focused, Pereira won both fights: once by judges’ decision and once by a devastating knockout.

In 2021, he became the first fighter in Glory Kickboxing history to hold two world titles simultaneously — in middleweight and light heavyweight — and decided it was time to reach for an even higher peak.

Conquering the UFC

His old rivalry with Adesanya, now the UFC champion, reignited his hunger. Adesanya mocked him publicly, belittled his past addiction, and claimed Pereira’s greatest achievement was “telling people in a bar that he once beat me.”

For Pereira, that was a red line. Opponents soon learned that mentioning his past only fueled his determination. He stormed into the world of mixed martial arts, and within a year, faced his old rival again — this time for the middleweight title at Madison Square Garden.

Adesanya dominated most of the fight, but with just two minutes left, Poatan unleashed a barrage of punches that reversed the outcome. The former alcoholic from a tire shop was now a world champion.

Although Adesanya won their rematch, it didn’t stop Pereira. He simply moved up a weight class and captured the light heavyweight title as well, establishing himself as one of the greatest fighters in UFC history — a symbol of a warrior’s body, a survivor’s soul, and the belief that even from the favela, one can reach the top of the world.

The Myth of Poatan

Pereira began cultivating an almost mystical image — that of an ancient warrior pulled from another era. Before fights, he follows a ritual: a frozen stare at the crowd, a pantomimed bow and arrow, a hand gesture resembling a tribal dance, and finally the battle cry “Chama!”

For him, it’s more than a slogan. It’s a reminder of his internal fight — the fire he learned to control rather than let consume him.

Behind all the spectacle lies a simple man: quiet, direct, and almost introverted. He lacks the ego and drama that define many fighters. After earning more than twenty million dollars, he began fulfilling childhood dreams and traveling the world. As his fame grew, critics speculated that his career might decline — as had happened to Conor McGregor, who struggled in the ring as he became a cultural icon.

Redemption, Rivalry, and Legacy

The critics were partly right. In March, Pereira faced Ankalaev again — and lost his title. A rematch was scheduled, and Ankalaev made a crucial mistake: he mocked Pereira’s childhood.

“I told myself I had to get him back,” Pereira said. “He can’t say I’ll go back to working in a tire shop.”

Pereira relished the opportunity to humiliate him — pointing mockingly as Ankalaev struggled to stand, likely disoriented after absorbing a brutal barrage of punches. The knockout was so spectacular that some commentators called Pereira the greatest Brazilian fighter ever. In a country that produced legends like Royce Gracie and Anderson Silva, that is an extraordinary honor — but Pereira’s journey isn’t over.

He now dreams of becoming the first fighter in history to win titles in three weight divisions. Immediately after defeating Ankalaev, he set his sights on the next goal.

“I want a massive fight,” he declared. “I want to face Jon Jones at the White House.”

The White House is expected to host a UFC event for the first time — one touted as “one of the biggest ever.” Jones, a heavyweight with only one career loss but a history of scandals, has announced his retirement but hopes to return for the mega-event, with Donald Trump expected to attend.

Pereira sees the fight as a major opportunity to elevate his legacy. UFC president Dana White has said he “doesn’t trust Jones” and therefore won’t offer him the fight. But with time until June 14, 2026 — and Trump eager for the biggest names — the possibility remains.

A Symbol of Hope

Even if that fight never happens, Pereira has already achieved something no one can take away. He has become a symbol of hope — proof that it’s possible to climb from the very bottom to the very top without shortcuts.

The man who grew up with nothing, worked in a tire shop, and drank to forget has turned his self-destruction into an internal engine of fire.